Hybrid hybrids

JIM WARD has been involved in the transport and logistics industry for 33 years. He found himself thinking about how much it has changed during this time, and was inspired to put his ideas to paper about what the future may hold.

June 5, 2037, 06:00, Greater Gauteng.

Tsepo picks his driver’s smart card (DSC) from its charging bank and makes his way to his clean, white Indo-Chinese/European truck. As he approaches, his smart card is recognised and signals the vehicle to start. The truck preselects neutral, confirms parking brakes are on, preheats each cylinder, unlocks the doors and starts up, immediately initiating a number of pre-trip checks.

The young man walks around the truck and trailer in sequence as it tests its own driving lights, wipers, headlamps, indicators, hazard lights and so on, idling quietly without visible smoke or any noticeable exhaust smell. The engine runs for a few minutes then activates an economy idle setting and switches to four cylinders.

Within the vehicle’s electrical system, while the 450 hp internal combustion engine (ICE) idles, six high-speed, super-cooled ECUs rapidly communicate with each other, checking a number of key variables – ride height, air-bag pressures, smart-braking activation, brake-pad and rotor thickness, air-reservoir pressure and all the normal engine checks including charge rate, air-filter restriction status, and the complex exhaust after-treatment system.

A few other factors are checked, too: rate of charge from solar panels, battery condition of the lithium-ion phosphate traction batteries, load and temperature status of the brushless DC drive motor and the myriad circuits in the dynamic regenerative braking systems. Several thousand items are checked in rapid sequence, in a go/no-go process that no human could possibly replicate in the minutes available.

After walking right around the combination, Tsepo climbs into the cab, already warmed up against the cold, and plugs his DSC into the dashboard. A twelve-inch touchscreen lifts out of the dashboard and lights up. His driver’s card carries with it a wealth of data, and plugging it in initiates a series of key events. First, his company starts paying him. The touchscreen is a high-definition display with a range of different scroll-down menus.

He checks some “soft news” items – two messages from his wife to call him, three from friends wanting to meet up, two football scores. These red-flagged messages mean he will be charged for returning these calls, and he will make them later.

He scrolls to some brief items of internal company news, two marriages, birth of a new son, 17 new vehicles arriving, an Honours Degree in Logistics awarded, a new driver-awareness training programme, and a message from HR asking him to visit after he clocks out that evening and sign certain pension documents. These are flagged green. If he wants more information, he can touch the screen to expand the details and make free calls. The menu offers a mixture of private messages that only he can see, and group messages open to all drivers, identifying him from the DSC.

He then starts his vehicle pre-trip process, scrolling to the tyre-check page. This flags every wheel position, the ten rim-mounted RFID sensors informing that all the tyres are at the correct pressure by showing blue on the cold-tyre display.

Graphics display fuel and battery levels, air temperature and outside camera views. If he neglects to open any safety-critical items, the truck’s brakes will not release and his pay is docked.

He progresses to the next sheet; a quick series of 20 random questions to answer in one minute. Some test logic, others test reaction times or eyesight, or are a simple check of observation skills; today asking in which bay the truck is parked, and what time he started the driver suitability test.

If he doesn’t complete the test in a minute, or scores below 19/20, he has one more chance on a fresh test, but if he fails that one, the truck will shut down, alerting the control room in a flagged message “driver unfit for duty” and explaining why.

It will not restart with his DSC; he will be replaced and sent home, unpaid, unless he fails reaction-time tests, when a medical check will follow. Anyone failing three times in a month is sent for retraining.

Tsepo is a master at this; he’s bright, alert and aware, and finishes the test in 53 seconds, scoring 20/20 and then, with his heart beating a bit faster than usual, he takes a deep breath and relaxes. He scrolls to the most important page – his route for the day.

It opens a detailed GPS map, with text boxes indicating the probable weather on route, traffic delays and deviations. He knows his route will avoid all possible right-hand turns to save fuel and maximise average speed.

He may travel further than he needs to, but, within the company, maintaining the target average speed is one of the top-measured and reward-weighted performance indicators. There is also important load data.

His trailer was pre-loaded the previous night by autonomous forklifts. The electric drone lifts all operate in total darkness, roaming silently through unmanned security points to pre-ordained picking points, uplifting pallets, then following buried electrical guides to the exits, and GPS guidance to the exact parking bay and precise trailer position, loading the rig from both sides simultaneously.

Proximity sensors take over two metres from the vehicle, with critical data points guiding them exactly between headboard and tailboard positions, and memorising each loading position. Loading damages are almost non-existent.

Tsepo’s trip schedule shows he has a mixed load – both “self-locking” and strap-down pallets. The self-lockers are lightweight pallets made of recycled materials with embedded steel plates set in their base, engaging with electromagnets set in the flat deck. They cannot move in transit and are self-securing. He also has eight old-fashioned pallets needing to be strapped down.

He enjoys this process; it’s one of the few physical activities left and reminds him of his heritage, and stories his grandfather told him about strapping loads and throwing tarps, when driving trucks 55 years ago.

He walks to the rear of the trailer and straps down those pallets, the difference being that once he threads the cargo strap through the winch it activates automatically and tightens to a pre-set torque load – no ratchet and steel bar like old-fashioned load locks.

Bright green LED lamps illuminate the trailer sides, meaning that the maglocks are on, self-lockers are secure and winches are tight. He climbs up into the cab, releases the park brake, checks forward, rear, and the bird’s-eye camera displays. He then moves off, using only idle power.

This load must be covered, so he’s directed to a drive-through trailer security section (TSS). As soon as he parks on precisely the right spot, loading lights above switch on, telling him to wait.

A lightweight, rip-proof, polyacrylate clamshell covering lowers automatically from overhead gantries and is placed onto his trailer. All trailers are one size. The cover’s roof consists almost entirely of flexible solar panels. The cover engages snugly with the sloping aerodynamic headboard, shaped like an aircraft wing, rising at the front and tapering down towards the rear.

The clamshell covers the whole load, and greatly reduces the air gap between truck and trailer. It is automatically secured with a set of electronic locks along the trailer. Customers have the codes required to release the locks, and all DCs have similar trailer-securing facilities. They remove trailer covers, stack and store them, and can change the photovoltaic branding for a different load. Drivers may not leave their cab in a TSS.

Load covering takes three minutes, due to a series of automated tests, checking electrical connectivity between the solar panels and deep-cycle batteries, but the clock is running and he is keen to get moving.

Fully loaded, the power-split hybrid truck calculates the payload via its airbags and complex algorithms involving tractive and braking force, and switches to full-electric start; something it will use for every pull away from standstill throughout the day.

Drawing power from truck and trailer batteries, with contacts within the fifth wheel, the brushless DC electric motor will quietly take the vehicle from standstill to

30 km/h. The truck then switches to hybrid mode, alternating between diesel and electric motors, or both. Tsepo is already moving out of the despatch yard and on to the road as the truck completes its communications checks.

He knows his route will have a number of hidden geo-fence checkpoints used to monitor his average speed, and that the vehicle is monitoring brake use, accelerator position, use of regenerative braking and proximity-sensing cruise control.

The vehicle accelerates quickly up to its cruise speed, on this road only 60 km/h, and the electric motor seamlessly disengages, leaving the truck running on its internal combustion engine (ICE) and AMT driveline.

He slows for the first set of lights; the braking energising the kinetic energy recovery system (KERS) and the DC motor converting into a generator, which charges a massive capacitor and his main battery pack, while shutting down the diesel engine.

His route is pre-set to the minute, and traffic lights are synchronised; as he nears them they turn green and he can power up again, briefly using both electric power and the ICE to regain his speed. He only comes to a full stop twice, as there are no right turns across oncoming traffic streams. Cable theft carried a treason charge after 2027, and the problem disappeared entirely.

After 20 minutes, he enters a faster arterial road and speeds up to 85 km/h, where the transmission gears down to 1 350 r/min (the slowest possible) automatically freewheeling on declines, and engaging the DC drive on inclines.

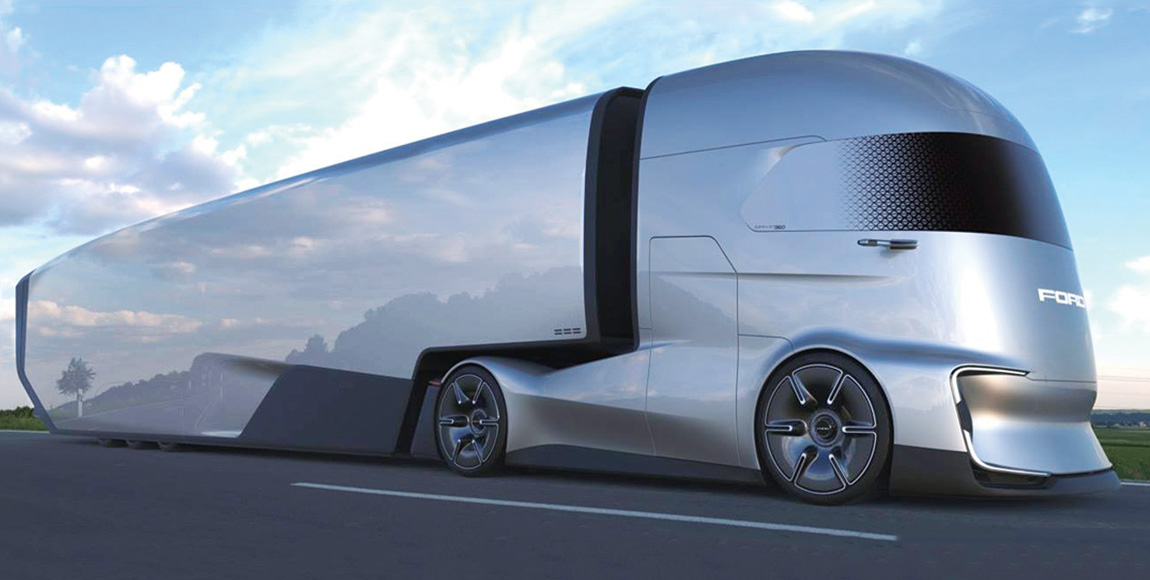

The truck and trailer creates minimal drag through the cool morning air, due to the trailer cover, minimal air gaps and wheel covers over the LP drive and trailer wheels.

Tsepo still monitors instantaneous fuel consumption and battery use, trying to get both into the green band. He aims for three steady green lights – ideal average speed, optimum fuel consumption and battery use, but to achieve this he must concentrate, using his multi-functional steering wheel and head-up display frequently.

There is an accident ahead; red lights flashing. He brakes hard, full regenerative braking charging the batteries, activating stage-four retardation long before air brakes are needed. KERS is at max energy now, and as he stops he can see the accident clearly. His drivecam is already recording the scene, triggered by the g-force of harsh braking.

A purple driverless sports car hit a pot hole, suffered a deflation and jarred its circuitry. This confused the satellite steering, which defaulted off the road, the vehicle bumping over the kerb and hitting a wall. The owner emerges angrily from the back seat of the car, where she was working on her laptop.

These American cars are insurance nightmares. It’s leaking vivid green battery gel and coolant onto the ground and steam is coming from the computer cooling pack. The car’s display and rear window is blinking rapidly: STOP fault! STOP fault!

He watches as his average-speed indicator flickers and changes from green to orange, and then red. He is already behind on the next checkpoint. He uses full power – KERS, ICE and DC to get moving again, drawing heavy current from the batteries and the huge capacitor to get the heavy rig moving and back up to speed as quickly as possible. The drive tyres chirrup in protest as the motor briefly produces 97-percent power, but if he misses the next waypoint time limit, he will lose pay.

After 48 km traversing the megacity, he begins seeing warning signs, alerting him to traffic problems up ahead. He presses “reroute”, and the GPS starts recalculating best alternatives. He knows the control room will have been alerted and will already be sending a revised ETA to the client because he might miss his offloading time slot.

The guidance system is highly advanced, coming up with two alternatives within seconds, both involving a time saving. He selects one and soon has to make his first turn across traffic, from a complete standstill.

The gap is long; he only needs to use 60 percent of the available torque to get the rig across the oncoming lanes safely. His fuel consumption target has gone orange, target fuel consumption has been exceeded, but he knows the accident and route change will be taken into account, resolving to drive as accurately as possible for the remaining trip.

The voice communication system blips once. It is one of his girlfriends in the control room, advising him to use the second entrance to offload as they’ve secured an earlier space for him at trailer security; so he can jump the queue and get his cover lifted off earlier than planned. This puts him back on schedule for the offload, and he sends her a quick “thank you” emoticon, then starts calling up the numbers from his messages received that morning.

Like several schoolmates, Tsepo was recruited straight from school after showing a flair for geography and engineering science, and completed a two-year intensive training programme on maximising Smart Truck benefits. He loves his work and is exceptionally good at his job. He gave his truck his clan name: Biyela, and its emblazoned across the doors, alongside Ndebele artwork.

Old drivers claimed it was much harder in their time, with crash gearboxes and drum brakes, but secretly he thinks they’d never cope with the multiple inputs, complicated controls and checks and measures that are part of modern trucking. He’s monitored every minute of the day and really has to concentrate.

In the cover-removal entrance, he waits for the customer to release the electronic cover locks in the trailer floor. He then walks around the trailer, the DSC releasing the electromagnetic locks and power winches, preparing for the drone forklifts to offload after the clamshell removal.

A big change came in 2029, when logistics began to attach value to a driver’s time in an unprecedented way, when The National Demurrage Act of 2028 allowed transporters to charge for standing time.

Suddenly, turnaround times improved dramatically, and the bad old days of drivers dozing in long lines, waiting for hours before offloading, disappeared overnight. The trucks were simply worth too much and the assets needed to be sweated to repay their R13-million cost. He smiles, thinking about men sleeping and cooking in their cabs for weeks while waiting at border posts.

He suddenly remembers something he daren’t forget; one of the red-flagged messages was his wife, Nomthando, wanting him to buy bread and milk on the way home. The cover is secured, and he watches carefully as the route guidance plans his homeward journey and begins alerting him to peak afternoon traffic.

Just another day for a professional African truck driver in 2037.

Published by

Focus on Transport

One Comment

Leave a comment Cancel reply

focusmagsa

Future Trucks

Be interesting to come back in 20 years and see what of Jim’s predictions have come to fruition.

Unfortunately however, I may not be around to see them.