A watershed or just more of the same?

A watershed or just more of the same?

Before the Minister of Finance, Tito Mboweni, took the floor on February 24 to deliver the 2021 Budget Speech, the financial services group PSG noted that this year’s edition would be a watershed for the country … JACO DE KLERK discovers that it wasn’t the turning point that so many hoped for.

George Glynos, MD of the boutique financial market research and analysis house ETM Analytics, says that he was a little perplexed this year by some of his colleagues who rated this year’s Budget Speech six or seven out of 10. “If this is a seven out of 10, what on earth does a two or a three out of 10 look like?”

What would a seven to 10 out of 10 look like?

“So, I asked myself what would a seven to 10 out of 10 government look like? It would be a government that had plenty of reserves to withstand a shock and have the ability to not just tap into its balance sheets,” Glynos explains. “But it would also have other resources, such as quantitative easing and other policies that it could deploy.”

He adds that these governments won’t mis-save, typically, and they try to keep their debt levels well contained or even low. “You think of a country like Germany, for example, that was running budget surpluses until this latest crisis. Even though it had access to very substantial resources, it still felt the need to behave responsibly and take down its levels of debt.”

“The net result was that Germany was one of the first countries that experienced the benefits of a negative interest rate. In other words, people pay them in order to lend their money. It is a bizarre concept, but one that exists.”

Glynos adds that these governments respect taxpayers and use the funds responsibly, curbing corruption. “Relative to the size of the economy these governments are typically a little smaller and they participate in, but do not necessarily run, things like state-owned enterprises (SOEs).”

Their participation in these SOEs is to ensure that there is a political imperative that is introduced in the economy via these institutions. “They become enablers of growth rather than the drivers of it and they are very good at attracting private sector investment.”

And four to six out of 10?

“A government that scores anywhere between four and six out of 10 is one that is happy to run budget deficits, but a deficit that is for the most part sustainable,” Glynos points out, adding that these governments mostly manage to contain debt levels but are more vulnerable than a higher-ranking government.

“It enjoys, at the very least, stable debt servicing costs in that they are not diverting very scarce resources in directions that aren’t productive. They centralise power, but they do seem to find a balance about it. They opt for regulation, but not too much. And they believe in large government in certain spheres, but don’t overdo it.”

Glynos explains that these governments are reliant on higher degrees of taxation, but not to the point where they cripple economic growth. “This is probably the bracket where most countries in the world reside and it is one where South Africa resided for quite a long time.”

South of four?

Glynos says that in the third and final category, which scores between one to three out of 10, the government has lost control of its debt trajectory. “They become rather large dissavers and they ultimately land up consuming the savings base of a country,” Glynos notes. “As a result, they need to levy higher tax burdens on the private sector and they have an inherent distrust of the private sector.” He adds that these governments see SOEs as part of the range of levers that they can pull in order to achieve their political ambitions.

“Ultimately if you get such a behemoth like this, it becomes very difficult to manage and, of course, you get creep in terms of how expenditures get deployed. And so irregular expenditure starts to ramp up, the disrespect to taxpayers starts to increase and the net result is that you find yourself in a position where the funding and running of a government budget become increasingly difficult.”

In light of all these points Glynos scored the 2021 Budget Speech two out of 10. “It is a poor number and a deterioration from last year. I’ve been told that I am unkind because we are in an awkward situation,” he explains. “Yet, if that were true, can someone please explain to me how a country like New Zealand just experienced a credit rating upgrade?

“They’ve lived through the same pandemic we have. They were not subject to any different international demands that we were, they also locked down just as hard (if not harder) than a lot of other countries in the world. And, yet, they have still managed to come out of this in a manner that has allowed them to secure a credit rating upgrade.”

A long and difficult road ahead

“The recession we found ourselves in a year ago, along with the Covid-19 pandemic and strict lockdown regulations, has taken its toll. Though the budget brings some relief, it is also a headache as we see years ahead of money being sunk into failing SOEs that should be restructured or closed,” says Julius Kleynhans, Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (Outa) executive manager: public governance division. “Much of this Budget is treading water.”

Debt-service costs are increasing as a percentage of the budget. Although this is increasing at a lower rate than previously predicted – which will reassure the ratings agencies – the size of the total debt is heading for an enormous R5,23 trillion by 2023/24. Those debt costs are slowly edging out social spending. In 2019/20, debt-service costs (at R205 billion) were less than spending on health (R222 billion) and social development (R285 billion), but by 2023/24, debt-service costs (R339 billion) will be higher than spending on both health (R245 billion) and social development (R325 billion). “Of course, such figures aren’t sustainable,” Kleynhans points out.

Glynos adds that Covid has induced a big hit in the budget deficit. “But – even prior to that – we were talking about substantial budget deficits that hadn’t been seen in decades. We had lost some of that fiscal control that had become synonymous with South Africa from 2002 to about 2007. Can you imagine a South Africa that was producing budget surpluses?

“And, yet, that was what was happening in the times of Trevor Manuel and Thabo Mbeki. We were running budget surpluses, we were enjoying credit ratings upgrades, we were paying down debt and we were therefore able to divert expenditure to places where they were needed the most and for productive means within the economy.”

Glynos notes that one of the key indications that South Africa is steadily losing control is the inability of the country to run a primary budget surplus, which is the bare minimum required to be able to pay down debt. “This means that we are constantly taking on more and more debt and explains why South Africa’s debt trajectory has been on a steady rise over the past 10 years, showing no signs of stopping.

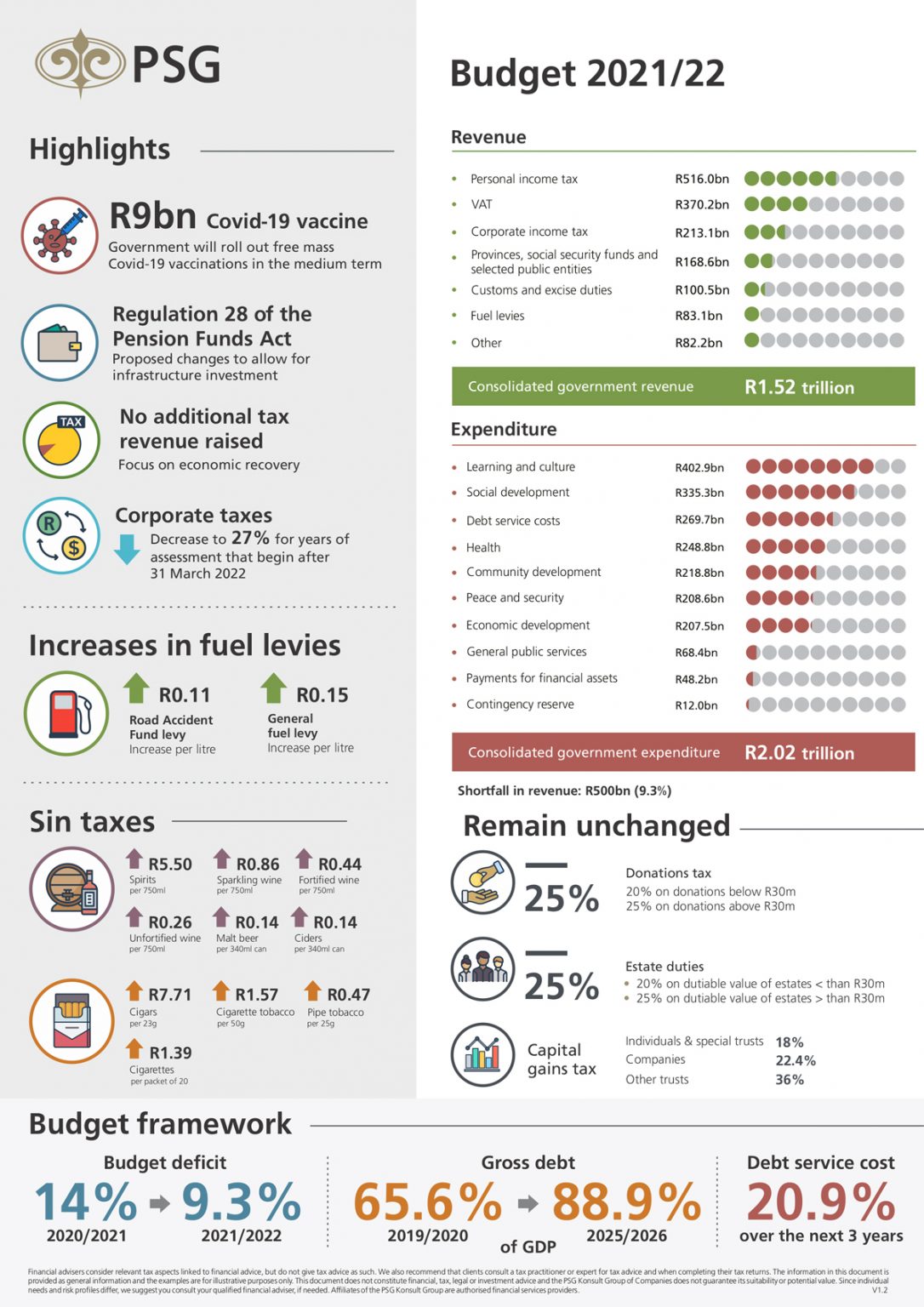

“The fact that we cannot run a primary budget surplus means that our debt servicing costs remain a huge problem and is becoming one of the fastest rising (if not the fastest rising) line items in the budget. If you look at the average debt service cost, as a share of the complete tax revenue, in South Africa, you are talking about a figure of more than 20%, on average, over the next three years. So, 20% of tax revenues are going to be spent on servicing debt. That money could have been spent so much more productively.”

The fundamental problems remain

Outa notes that failing SOEs continue to haunt the Budget, and the list of their problems makes dismal reading. “Rather than seeing expedited structural reforms, we see annual increases and ad hoc injections of capital from the fiscus to unviable institutions.

“Eskom is still on almost perpetual life-support from government (R56 billion in 2020/21, R31,7 billion in 2021/22) and is also borrowing more to meet debt payments. The SAA bailout of R16,4 billion over three years, announced in last year’s budget, remains but, as predicted, SAA now needs more: R19,3 billion, although this isn’t (yet) in the budget.

“The Land Bank is bailed out. SABC, with arguably a more important public mandate than SAA, is retrenching staff. Airports Company South Africa is selling non-core assets to make ends meet; but in a poorly timed move, Arts and Culture announced that two airports would be renamed.

“Government capacity is still lacking at every level, which affects every programme from vaccine rollout and early childhood development programmes to mega infrastructure projects,” Outa notes.

Some encouragement

Outa highlights that it appears as if government has taken note of the anger from taxpayers over suggestions of tax increases after years of unrestrained waste and looting. “They backed down on last year’s proposal to increase taxes and on recent hints of increases to pay for the Covid-19 vaccine.

“Instead, there is a little tax relief for individuals and businesses, which is welcome. Government has found sufficient vaccine funding, although this indicates a two-year rollout.

“SARS gets an extra R3 billion over three years for a new unit to ensure tax compliance of those with wealth and complex financial arrangements. The Department of Justice gets R1,8 billion to combat crime and corruption, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the money will be applied where it’s needed most.

“The Department of Tourism has reprioritised R540 million over the medium term to establish the Tourism Equity Fund and support tourism recovery. While we welcome the support for this crucial sector, we are concerned that this may mean that the department will acquire equity stakes in tourism enterprises, if businesses must sell a stake in their enterprise to get help.”

Another benefit was the R1,8 billion allocated to curb grey imports and illicit cross-border activities, which the Automotive Business Council – Naamsa – welcomes. “Grey imports have a massive negative impact on the automotive ecosystem in South Africa and cost the fiscus an estimated R3,8 billion annually in uncollected taxes,” it points out.

“More than 300 000 of the 12,7 million cars on South African roads are grey imports. This figure is growing at 30 000 vehicles a year. Unquestionably, this has displaced new car sales and harms the country’s economy.”

Mikel Mabasa, Naamsa’s CEO, says that based on the suite of taxes applicable to new car sales locally, “we estimate that the impact of grey imports is costing the fiscus R3,8 billion per annum. This grows to over R4 billion when you consider the taxable income on corporate profits in the value chain.

“Grey imports within the automotive industry do not only rob the fiscus of much-needed revenue, but they also hurt job creation prospects for many young people who are currently unemployed. The importation of these illegal second-hand vehicles also aids criminal activity in the country and undermines road safety initiatives,” says Mabasa.

“To put the grey import challenge into perspective, from a business side of things, the average new vehicle market for 2020 is 28 500 units. Grey imports represent an extra month’s sales per annum. Effectively, grey imports represent 7,5% of total market and would be the third largest brand in South Africa by volume.”

Infrastructure investment to boost industrialisation

“Minister Mboweni faced the difficult task of balancing economic stability and the reality of an eroded tax base, escalating debt to GDP and struggling consumers and businesses,” Naamsa notes. “The Budget announcement of R791,2 billion infrastructure investment, supported by the government’s commitment to establishing special economic-zone industrial bases, will boost economic activities, industrial performance and will address the widening infrastructure deficit.

“In line with the country’s aspirations, the automotive sector has announced a range of investment opportunities to boost South Africa’s manufacturing capacity. Some of the automotive investments, announced recently by President Ramaphosa during his State of the Nation Address, include Toyota’s first production of hybrid vehicles in South Africa, local production of Nissan’s Navara, Isuzu’s D-MAX bakkie, and Mercedes-Benz investments. Furthermore, Ford Motor Company announced an R16 billion investment, which will create 1 200 jobs in the coming years.”

Still more of the same?

Naamsa notes that despite the government’s increased support during the pandemic, the country still faces severe economic challenges. “Recently, Statistics SA announced that the unemployment rate climbed to a record 32,5% in the fourth quarter of 2020 (from 30,8% recorded in the third quarter of 2020). This is the highest unemployment rate since 2008.”

The gross national debt is projected to stabilise at 88,9% of GDP by 2025/26; down from the previously projected 95,3%, but still dangerously high. “We are not a European country that can afford to run debt to GDP ratios of 80% and above,” says Glynos.

“We spoke last year about South Africa being one major crisis away from big trouble and we find ourselves there already. We got that global crisis. Perhaps we haven’t hit the full wall yet, but we have certainly brought forward the timeline of a possible fiscal crisis. South Africa was on a slippery slope towards that fiscal crisis before the pandemic. Covid has just fast-forwarded things. The fight for political legitimacy continues to erode the state’s capacity.

“I believe that the calamity has arrived. Unfortunately, nothing much has changed. We are heading towards a fiscal crisis and a debt default is potentially still on the cards.”

Published by

Jaco de Klerk

focusmagsa