State interference: Quietly killing industry

State interference: Quietly killing industry

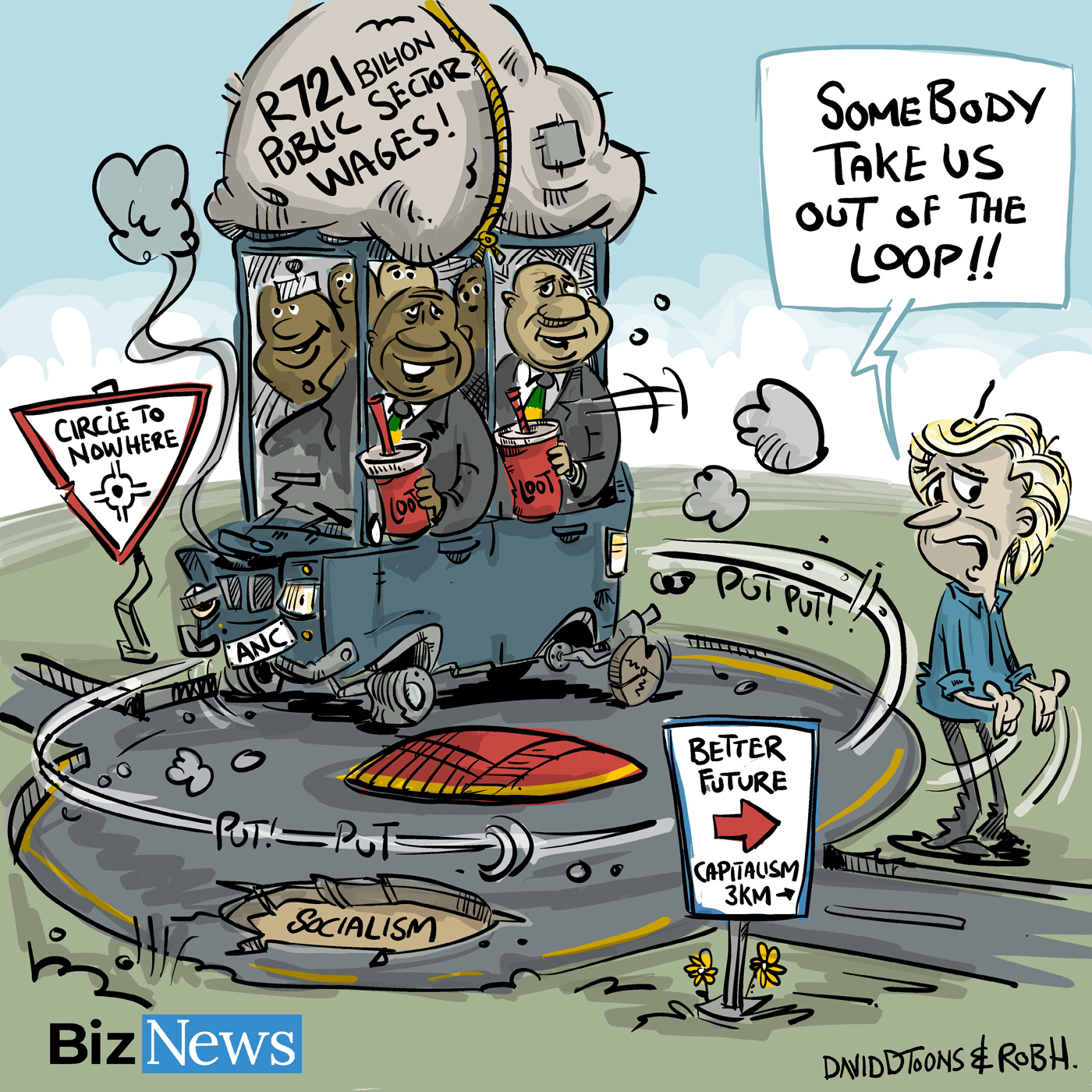

As South Africa faces mounting economic challenges, is it time to return to pure economic principles? NICK PORÉE explores how unchecked bureaucracy is crippling industry, competition, and national growth.

A simple classification of society by primary economic functions identifies three categories: producers (industry), consumers (customers), and administrators (government as regulators). Producers strive to make profits and survive by earning customer satisfaction; consumers strive to make the best choices in the goods and services they buy; administrators seek to create a playing field of public infrastructure and regulation on which the population can live in peace, harmony, and prosperity. In practice, individuals can be engaged in more than one category at various times, and government can distort the playing field.

Free enterprise consists of associations of people using the four factors of production – land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship – to create goods and services. Industry can be divided into sectors: extraction of raw materials (primary), manufacturing (secondary), and service industries (tertiary). The latter includes logistics, existing to facilitate the transport, distribution, and sale of goods produced in the primary and secondary sectors. The management of these activities coordinates and controls the actions of employees to produce profits and “private wealth” for the entrepreneurs and investors; management failure leads to losses and business closure.

As we are seeing a rise in interference in business by governments all around the world, it is as well to remember that the laws of economics are almost as immutable as the law of gravity, with fundamental principles based on efficient competition in markets. Success in competition for business is dependent on demand and cost-effective supply. Principles like the customer is king, sink or swim, sow if you wish to reap, winners and losers, and nothing is for mahala continue to apply irrespective of government policy.

Unlike competitive commercial business, the management of public enterprises and organisations is performed by bureaucracy; a system based on the delegation of power but without the disciplines of profit and loss, accountability for failure, or existence determined by customer demand. Land is treated as a free good to be used or not; labour is not selected and employed for qualification or performance; capital is derived from the public purse, not from earnings and savings; and entrepreneurship is not required, as there are no business risks.

Bureaucratic management depends on “policies” which may be described as “management or procedures based primarily on material interest” and are underpinned by regulations, not profit and loss. In the absence of profit motivation, the intentions of policy must therefore be evaluated by examining the plans rather than the highly theoretical outcomes.

The invasion of the productive sector by government promotes the use of State-Owned Companies (SOCs) to generate “private wealth” from state resources, without accountability.

The socialist model adopted in South Africa has the administrative sector (government) engaging in industry in several critically important production functions: electricity, railways, ports, and several other industries, using bureaucratic management instead of commercial discipline. We now have a curious situation where the government (Department of Transport and Transnet) is inviting Private Sector Participation (PSP) in the “production” of railway services, which should logically be a commercial private sector activity. The invitation is to “participate” in the uncompetitive supply of service (it used to be Public-Private Partnership or PPP — now reduced from partnership to participation, by invitation only).

This comes after the state’s “productive” institutions have virtually collapsed the economy with a shocking backlog of over R500 billion of debt and no accountability – a circumstance which could not happen in the productive sector. This effectively means South Africa Ltd (the fiscus and taxpayers) has been subsidising SOCs for the past 20 years. Our overall economic output has therefore been that much lower. The fact that this has been permitted, and has gone unreported, is only possible in a bureaucracy. In the meantime, private sector industries have largely abandoned the railway for inefficiency, are seeking ways to use neighbouring ports, and are incurring exorbitant costs for private sector road transport in order to retain their markets.

There can be no ethical reason for continuing the existence of wasteful, state-owned, pseudo-commercial activities. They should be dismantled and sold to commercially competitive enterprises that would return them to profitability, payment of taxes, and expansion of employment, instead of being subsidised in a glacial return to ineffectiveness, which will cost taxpayers further billions of rands. To create commercially sustainable railways, there is a need for total restructuring into an independent Network Management Unit, with an efficient and equitable train management system. Funding by government is required to restore the Transnet and Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA) railway infrastructure before private Train Operating Companies (TOCs) can invest with confidence in competitive train operations on the network. The independent Network Manager and regulators are best located in the Department of Transport (DoT), not the Transnet Railway Infrastructure Manager (TRIM).

At the same time, there is talk of industrial policy aimed at increasing the interference by government in the productive sector by spending public funds on business development and forcing localisation. The pseudo-entrepreneurial masterplans are supposed to create industries by handouts, irrespective of profitability or accountability for failures (the same process that collapsed the Land Bank and drives the poultry industry plan).

The Business Unity South Africa (BUSA) evaluation of the policy proposal gives warning of the negative potential of using policy manipulation and subsidisation instead of competition as the spur for economic development. The commercial banking system in South Africa has all the necessary funds to support entrepreneurial development where it can be shown to produce profit. The government’s planners have no way of identifying or measuring the highly theoretical outcomes of these policy “investments” and much of the same policy direction can be shown to have failed (witness the national debt) for contravention of the laws of economics.

The wise words of economist Ludwig von Mises are very relevant here, as he wrote in 1944, with an eye to the pre-war chaos, the causes of the war, and the future governments of Europe and America: “Economic interventionism is a self-defeating policy. The individual measures that it applies do not achieve the results sought. They bring about a state of affairs which – from the viewpoint of its advocates themselves – is much more undesirable than the previous state they intended to alter. Unemployment of a great part of those ready to earn wages, prolonged year after year; monopoly; economic crisis; general restriction of the productivity of economic effort; economic nationalism; and war are the inescapable consequences of government interference with business.” [Author’s note: as recommended by the socialist dogma]

This sounds very familiar and ominously like our current national downward trajectory. The continued recommendations of experts are ignored, so a return to economic principles is required to get the economy into production mode instead of relying on the fruitless processes of bureaucratic planning. Recovery requires the industrial sector to reassert itself to recover control of the means of production, throw off the barriers to competition, and redefine the roles of producers, customers, government, and the factors of production, in alignment with the laws of economics.

Published by

Nick Porée

focusmagsa