Revealed: how SA can achieve a functioning rail freight network – Part 1

Revealed: how SA can achieve a functioning rail freight network – Part 1

Do you fancy the idea of a functioning rail freight network in South Africa? ELVIN HARRIS certainly does. He believes that the solution lies in a direct government contribution to financing the network. This is Part One of a fascinating two-part series on the subject.

Let’s start with a brief history. South Africa’s railway system is almost 160 years old; it’s been at the forefront of economic, technological, social, and even cultural development since its inception. It is one of the oldest railway systems in the world and is one of the top 15 largest railways globally, with a network size of just over 30,000km of track.

Our railway system has evolved with the times. It has acquired many world-class technologies and processes from best practice around the world and it has also been a world-leader in several areas, such as heavy-haul operations and running extremely long trains.

Much of this success was achieved over almost a century (1910 to the late 1990s/early 2000s). I would argue that one of the most critical reasons why such successes were achieved by a railway system far removed from the rest of the world and developed on a Cape Gauge (1,067-mm track gauge) – quite distinct from most of the western world’s 1,435-mm standard track gauge – was due to the fact that from 1910 to 1980 the South African Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) authority was directly supported by funding allocations from the fiscus. There was even a special funding allocation granted to a statutory committee for the supervision, development, and maintenance of railway crossings and bridges.

This financial support lessened quite significantly between 1981 and 1990, the period of SAR&H’s successor entity, the South African Transport Services (SATS), but it did not disappear entirely.

Pursuant to recommendations made by the De Villiers Report on the Management of the South African Transport Services in 1986, Transnet SOC Ltd was formed as a public company (constituted in terms of the Legal Succession Act of 1989), with the South African government as the sole shareholder. Transnet SOC Ltd was, however, established with a mandate to be fully commercially viable on its own with no financial support from the State. Thus, all direct funding allocations from government to Transnet ceased quite abruptly in 1990.

The Legal Succession Act also provided for the separation of passenger rail services from Transnet SOC Ltd via the establishment of the South African Rail Commuter Corporation (SARCC) – now the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA). Only the passenger component of the railway continued to receive direct funding from the State after 1990, by way of an Operating Subsidy to SARCC and lately in the form of a recapitalisation of PRASA to fund a new fleet of train sets and the upgrading of its commuter network and train stations.

Not only did direct funding of Transnet come to an end (which meant no funding of the freight rail network within Transnet), but government also introduced the Transport Deregulation Act (1988) and the Road Traffic Act of 1989. To give effect to both these Acts, government continued to invest in the road network of the country (as it had already been doing since 1910) to enable mobility and flexibility for passenger vehicles. This was also done to improve the efficiency, flexibility, and reliability of the road freight transport market that now (through these pieces of legislation) could compete freely with the railways for freight cargo, due to most previous restrictions having been lifted.

THE INVESTMENT PICTURE FOR ROAD VS RAIL

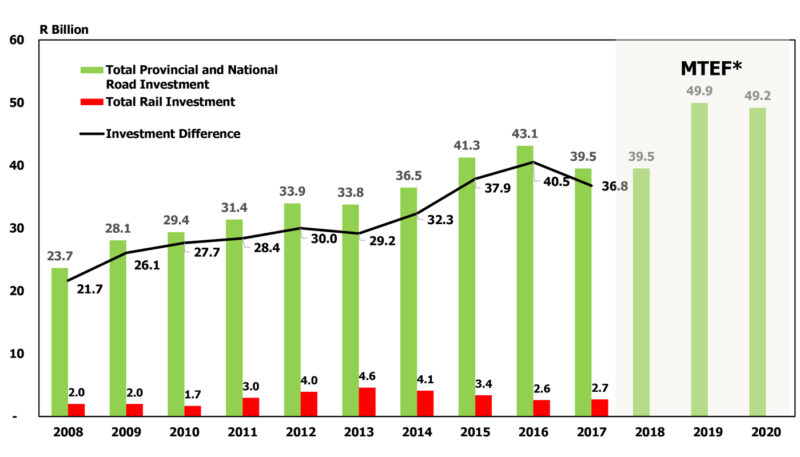

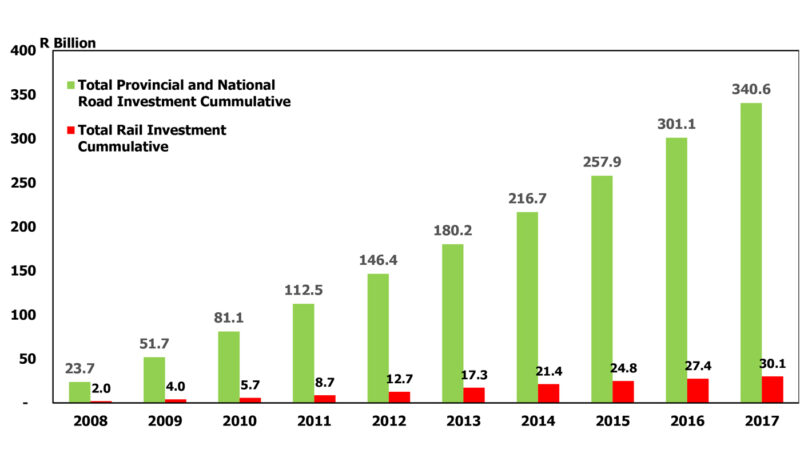

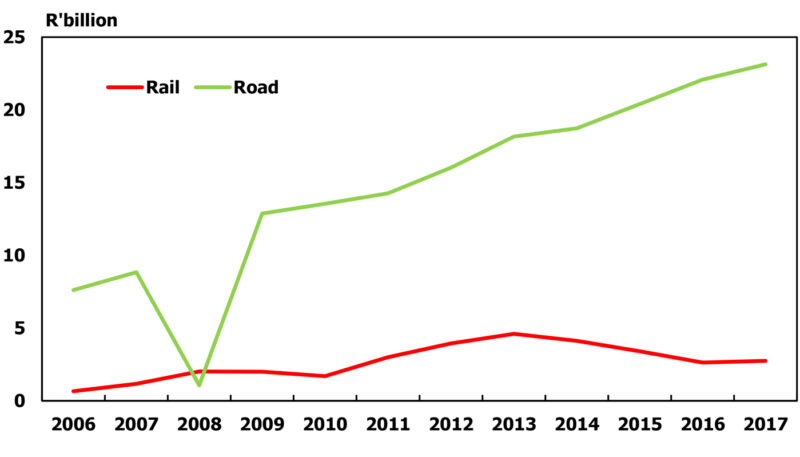

For the past 30 years, investment in the country’s roads has outpaced investment in rail by almost 10:1. In other words, there has been 10 times more investment into the road network than into the rail network.

Between 2008 and 2017, R340.6 billion was invested in road infrastructure, while a mere R30.1 billion was invested in rail infrastructure (Figure 1). Since 2009, the gap between road and rail infrastructure investment has been widening in the favour of road (Figure 2).

The maintenance and improvement of road and rail networks, meanwhile, have not kept pace with the growth in traffic and requirements for safe technical standards that need to be met to ensure the safe use of such infrastructure.

It is important to point out that the primary purpose of this article is firstly to highlight the significant discrepancy between direct funding from government to road networks as opposed to rail networks, and secondly to make a case for greater direct government funding to rail networks, given this skewedness over several decades.

It is in no way intended to suggest that funding should be taken away from road infrastructure and instead redirected towards rail infrastructure. What is being called for is a better balance between direct government funding to both road and rail networks, to enhance the efficiency and reliability of the total land transport system over time. This will support the competitiveness of the entirety of the South African economy and, by extension, the competitiveness of the SADC regional economy.

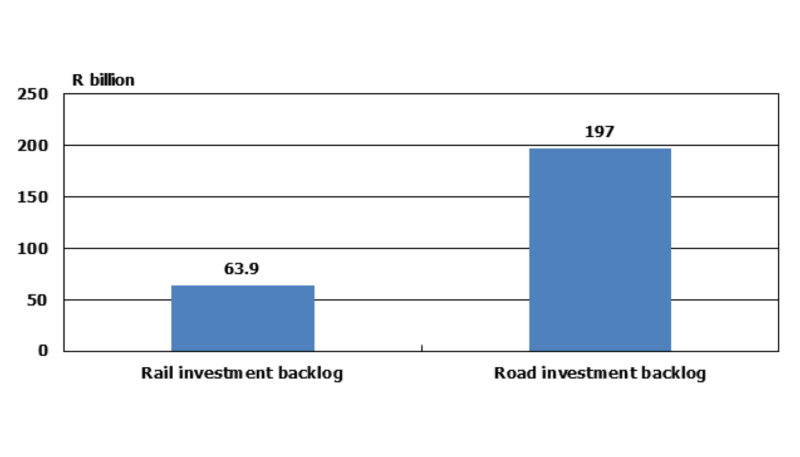

It is inescapable that the road networks themselves, despite being advantaged over many decades, still require significant amounts of funding for backlog maintenance, not to mention investment for new road infrastructure capacity as the networks suffer inevitable wear and tear and as the economy (and the population) continues to grow over time. The backlog in road infrastructure is, in fact, three times that of rail (Figure 4).

If our logistics system is to make any serious contribution to the competitiveness of the South African and regional economies, the generally poor state of our roads must be addressed – less than 50% of SA roads are in good to very good condition. Furthermore, any new road/roadside infrastructure has to be correctly and appropriately maintained in the future. This must be done with a clear intent to prevent any backsliding on the kinds of maintenance regimes that have led us to the present-day situation – a situation which, by the way, is most likely already much worse in 2023 than it was in 2013.

Compounding the significant challenge of less than half the country’s roads being in a good or very good condition, the forecast for road freight traffic growth on these roads is estimated to rise to 900 billion tonne-kilometres over the next 25 years.

Of this growth, heavy commercial vehicles are expected to outpace the growth of light and medium commercial vehicles, which will put even more pressure on South Africa’s road network – such as it is! This does not seem to be a sustainable scenario, and funding all this future requirement for road infrastructure is going to be extremely challenging.

Our only viable option is to significantly increase our spending on rail infrastructure to essentially tackle three core dimensions:

1) Improve and increase capacity on the rail networks in the short-term (primarily maintenance backlogs and some investment in new additional capacity) to arrest their decline and enable an early shift of lost traffic back to rail.

2) Continuous investment in upgrading the rail networks, in order to keep pace with economic growth and market demand for rail-friendly cargo going forward (lest we slip backwards and relive the whole cycle).

3) Keep up with proper maintenance regimes and continuous upgrading of rail network capacity, on the back of a good foundation established with the aforementioned continuous investment upgrading phase.

Where will the money come from?

How should this rail network deficit (vis-à-vis road network funding), maintenance backlog, and new capacity investment be financed and funded, though? It could be tempting to throw our hands up in defeat and say that neither Transnet nor the State has the financial resources to undertake the required investment into the rail networks, so we cannot do much more than be bystanders watching a figurative train crash unfolding in slow-motion before our very eyes.

It would be even more tempting to believe that the panacea for the daunting problems facing road and rail networks (especially the railway system) is to open everything up to the private sector and let private sector investment flood in and crowd out public sector investment.

A do-nothing approach and defeatist attitude are clearly not the way to go and not very “South African”, with our can-do attitude that enabled us to defeat Apartheid and set our nation on a new trajectory to the benefit of all who live here.

Opening the floodgates for the private sector to come to the rescue – as unpalatable as that might seem to certain groups of stakeholders – is a far better option than the do-nothing approach. One must consider the current environment, where Transnet is heavily indebted (it currently carries a debt burden of between R130 and R147bn according to recent statements from the chairperson of the Transnet Board of Directors and the Minister of Public Enterprises respectively) and the National Treasury is struggling with recurring revenue shortfalls and ever-increasing government expenditures.

National Treasury has also reported that the government has already spent R331bn on bailing out state-owned enterprises (SOEs) over the past 10 years since 2013. Transnet only received R5.8bn of this money in 2022, half of which went towards repairing infrastructure damage (mainly to the railway network) caused by floods. The other half was used to purchase spare parts for locomotives from China’s CRRC Corporation (according to press reports). These were both very specialised instances and have been the only financial support given to Transnet by government in almost 30 years.

Eskom, meanwhile, has received the bulk of the R331bn of government’s financial support over this period. One could argue that Transnet didn’t need government financial support or subsidies before 2022, and thus the government was correct not to allocate any funds to it. This would be a convenient argument to make, but an erroneous one. Because it was believed that Transnet was doing well financially, a position was taken that Transnet did not need any funding support from government and that there were many other more urgent needs. These included education, healthcare, housing, social grants, and funding for bailing-out SOEs that were in desperate to catastrophic financial predicaments. Eskom, SAA, the SA Post Office, the SABC, and Denel all spring immediately to mind.

While this may be partially true, it is a rather convenient position to have taken. The fact of the matter is that, since Transnet SOC Ltd was established, government has invested 10 times more money on roads than Transnet has been able to do on its own in the railway network. Government inadvertently set the country on a path where it became obvious that road transport – underpinned by government investment in the local, provincial, and national road networks (inclusive of toll-road concessions financed by the private sector) – would be extremely competitive against rail transport.

This was a noble idea when South African Railways and Harbours and South African Transport Services carried or controlled over 90% of freight traffic in the country. Unfortunately, the pendulum has swung too far to the other side from the heady days between 1910 and 1980, when rail transport had a chokehold on the land transport system.

It is quite telling of how serious the disparities in the land freight market are, when one realises how much of the so-called “rail-friendly cargo” is actually carried by road. This is primarily due to cost advantages offered by road haulers – as a result of the investments made by the state in road transport networks – but also due to service-related problems experienced by customers when transporting cargo by rail.

Freight rail has been asked to compete with road freight transport for the past 30 years with very little to zero financial support from the State. Freight rail valiantly fought this fight for two decades, but since about 2010 this has proven too much. The system is now crumbling and appears to lack the capacity to convey any new tonnes, while every new tonne of freight traffic seems to automatically go to road transport.

This has the knock-on effect that the road networks continue to suffer more damage and customers keep having to pay higher than necessary prices for transport and logistics. South Africa needs to get out of this vicious cycle or face a potential economic disaster. Our only viable option, as indicated earlier, is greater investment in the freight rail network – starting now!

This article will be continued in the next issue of FOCUS.

Sources: National Treasury and Creamer Media’s Research Channel

Published by

Elvin Harris

focusmagsa