Rail reform in name alone?

Rail reform in name alone?

For all the government’s talk and idealism – promoting Localisation Master Plans as the solution to South Africa’s manufacturing decline – politicians and bureaucrats may be better served by focusing on low-hanging reforms… to focus on just one area: rail. So says CHRIS HATTINGH.

Selling Transnet’s rail networks to private competitors in practice, not merely in name, would be a great start towards unlocking the country’s real trade potential. Doing so would also lead to lower transportation costs, protecting poor-to-middle-income consumers from at least some of the inflationary pressures that will be with us for the foreseeable future.

In April, Transnet Freight Rail invited bids from the private sector to operate 16 slots along its container corridor between Gauteng and Durban, and the south corridor between Gauteng and East London. The sale of the slots will be for a 24-month pilot phase until 2024. But investing in networks and equipment that will last for many decades makes little sense when your contract runs for just two years. Given the dismal performance of the country’s state-owned entities, would anyone want to sink millions in capital investment into a system that Transnet can simply take back and run, or rather, run steadily into the ground?

Mesela Nhlapo, CEO of the African Rail Industry Association (ARIA), has indicated that the number of train sets available will effectively be limited to those previously applied for in other projects that have not been deployed. The ARIA estimates that every 50-wagon train set costs up to R200 million, and each operator will require three train sets per slot, pushing the price per operator to R600 million.

Once slots on the networks have been sold to third parties, Transnet will remain as the custodian of the infrastructure. It will also continue as the dominant operator, giving third parties limited access to its infrastructure. Perhaps most crucial, and concerning, is that Transnet will retain full ownership of the rail network, as well as responsibility for its maintenance. Third-party operators will also have to accept the state of the rail infrastructure, but ARIA says this is in contravention of the national rail policy approved in March. Confusion reigns, and this is hardly a situation into which either local or foreign investors will want to wade.

With these requirements, this is not an environment likely to entice real private sector participation or meaningful activity. Indeed, the cards may already be stacked in favour of those with the necessary political connections, ensuring that they and their associates receive the most lucrative contracts.

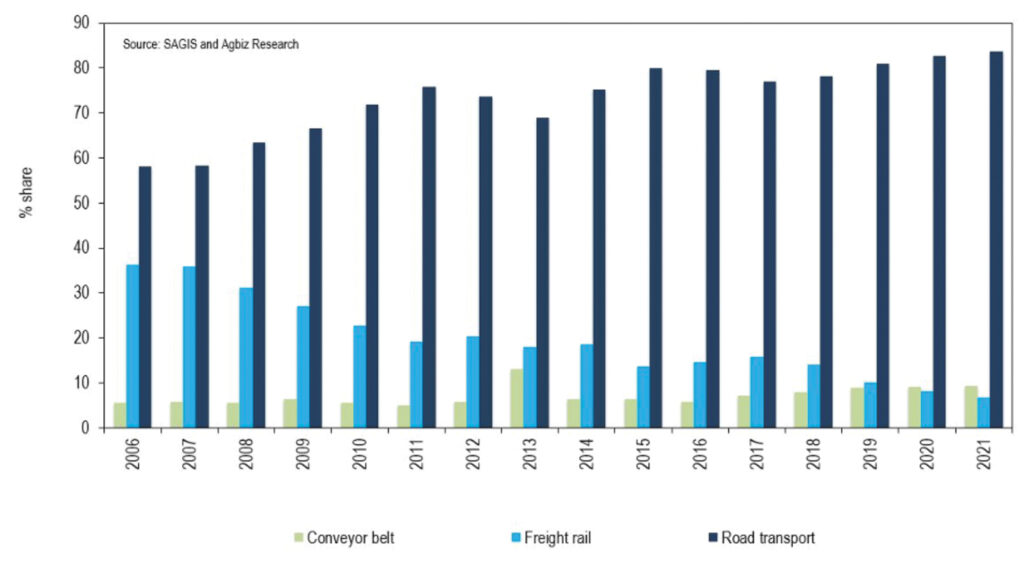

Much of Transnet’s rail infrastructure has been stolen. With proper security this could have been prevented. But the company’s widespread inefficiency has resulted even more from the State seeing it as good and proper to itself play a central role in transporting goods and an oversized role in “managing” the whole economy. Graph 1 shows the massive decline in the use of rail to transport maize and wheat. This is the unavoidable consequence of the implementation of the ruling party’s ideology.

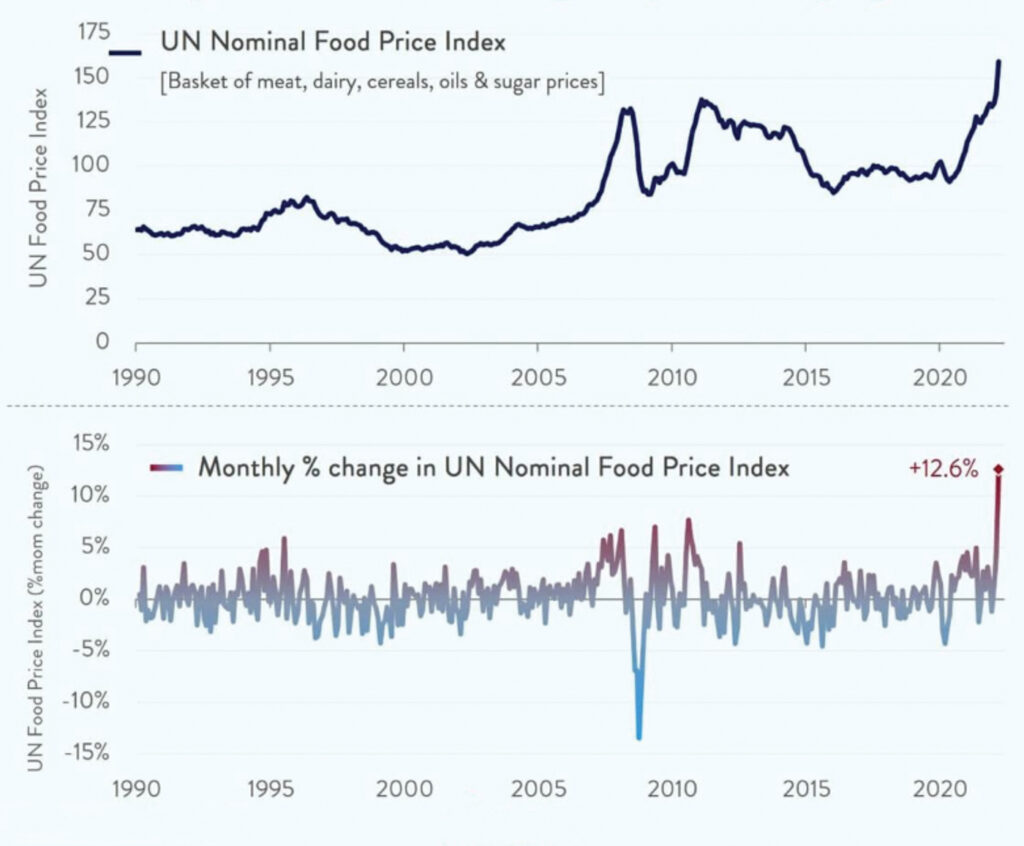

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has boosted the prices of global commodities. But South Africa, as a consequence of the government’s ideological and policy choices, has once again shot itself in the foot and been unable to gain the full benefits of higher exports. Total freight rail volumes declined by almost 14%, from 212.3 million tonnes in 2020 to 183.29 million tonnes in 2021. The coal, chrome, iron-ore, and manganese mining sectors reportedly lost between R39 and R50 billion in export earnings over the same period as a result of Transnet’s rail problems.

In the context of elevated global food (Graph 2) and oil prices – and with the ripple effects on trade from China’s “zero-Covid” stance likely to impact supply chains – governments can ease the pressure on consumers by removing the numerous barriers that they themselves have imposed over many years. For South Africa, this means fixing fundamentals like trade infrastructure.

Had our rail networks been more reliable or, indeed, simply available for use, more options would have been available to companies, farmers, and freight transporters. When hit by unexpected global events or unforeseen natural disasters, reliable basic infrastructure is crucial. In the latest example of South Africa’s policy choices being exposed to devastating effect, Durban port’s current backlog of 8 000 to 9 000 containers could have been considerably reduced, had companies been afforded the “luxury” of utilising more rail, rather than increasingly having to rely on roads.

Localisation Master Plans will be enforced either through subsidies for designated products (“champions”) or higher tariffs on imports, which will further increase prices and inflation pressures. They will not re-industrialise South Africa, nor achieve substantive growth. To achieve those goals, we need to get the basics right. Replacing simple lip-service with real rail reform would be a good place to start.

Published by

Chris Hattingh

focusmagsa