Book review: Phoenix Buses – Social Space and Pride of a Community

Book review: Phoenix Buses – Social Space and Pride of a Community

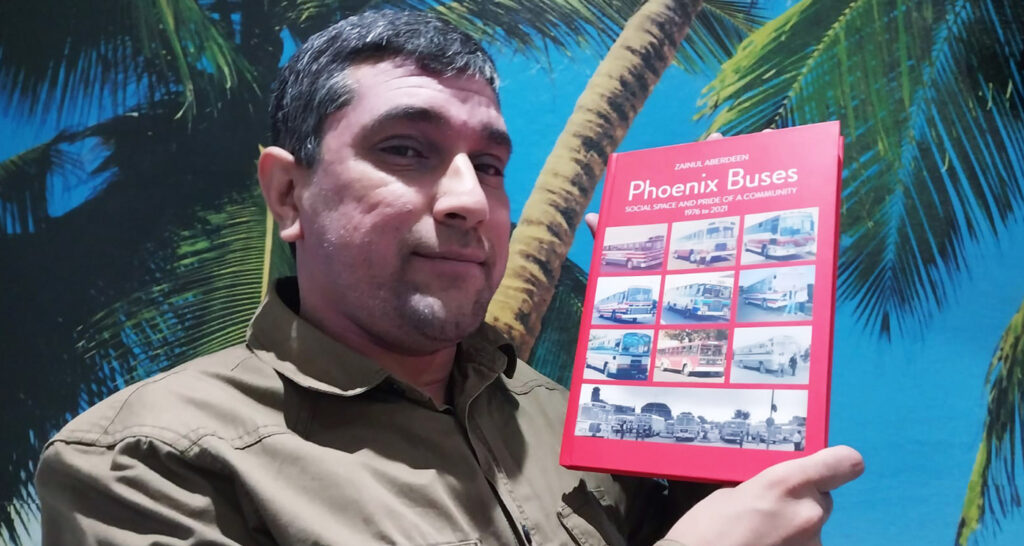

Following the success of his book, Indian Buses – the History, the Memories, the Personalities, Zainul Aberdeen has penned a second one: Phoenix Buses – Social Space and Pride of a Community. VAUGHAN MOSTERT, who lectured on public transport issues at the University of Johannesburg for nearly 30 years and penned an extremely popular FOCUS column called Hopping Off for many years, has reviewed the new book.

It was a privilege to be asked to review Zainul’s book, which not only records an important chapter in the history of public transport in Durban but, perhaps unintended by the author, raises issues that are highly relevant to the future of public transport in South Africa.

Even superficial readers who might have no strong interest in transport itself will benefit from reading this book. They will be touched by the stories and recollections of the everyday lives of a community of ordinary, humble people of modest income. Not being able to afford cars, they still needed public transport to travel to work, to school, to shops, and to visit friends, as well as to places of worship such as the temple, the mosque, and the church. They were able to enjoy weekend outings to the beach and places of entertainment, as well as special trips to attend funeral ceremonies and sports events.

That they were able to do so for affordable fares on buses that received no subsidy from any source is entirely due to the enterprise of individual bus operators. The casual reader of Zainul’s book cannot fail to be moved by the accounts of these pioneers, who from the earliest days had to overcome personal hardships to start a bus service. Often this was achieved with a single second-hand vehicle, sometimes either driving and maintaining it themselves or with help from family and friends, and thereafter slowly building up the business to a much larger fleet.

The book also describes the stories of the workers in the industry and their families – the drivers, conductors, cleaners, mechanics, rank masters, and others – anecdotes about their human characteristics, their children’s birthday parties, and their affection for the buses they drove and worked on, expressed by means of decorations and exotic names. All these stories, combined with hundreds of photographs, testify to the unique and rich interaction between the industry and the close-knit community that it has served for over 100 years.

But all of this seems to have come to an end – or has it? I believe that the future holds a lot of promise for the revival of this particular industry; this, provided a number of major impediments are robustly dealt with, could spell the renaissance of public transport throughout South Africa.

The book is not about politics – its title limits it to ”social space and pride of a community”, which the author covers very well. I would, however, like to focus a bit on the way in which the government of the day squeezed the Indian community, sandwiching them into areas not of their own choosing and then rubbing additional financial salt into the wound by failing to support them with affordable public transport. This injustice continues to the present day, affecting not only the Indian community but millions of public transport users all over the country.

The final chapter of Zainul’s book, titled Demise of the Phoenix bus companies, lists a number of factors that have influenced developments over the years. The last paragraph of the book is quite telling: “Perhaps the most important factor that could lead to the total demise of the Phoenix bus companies is the Go!Durban Integrated Rapid Public Transport Network (IRPTN) or Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) which is set to commence in 2022… Despite all the literature on the IRPTN, no mention is made of the role private bus owners in Phoenix will play or if they face extinction.”

This quote is absolutely correct, and I would suggest that it becomes one of the grounds for legal action against the municipality. Having said that, I would like to add a number of other factors that also need to be dealt with urgently, to the benefit of public transport users all over South Africa:

Systemic inequality

South Africa is known to be the most unequal country on earth – an unwelcome distinction that is unlikely to change anytime soon. It is a worldwide phenomenon that bad public transport and inequality tend to go hand-in-hand. What makes SA unique is the effect of forced removals on the population, which resulted in longer journeys and higher costs. The Indian community in Durban (the largest Indian community outside India, we are told) was particularly hard hit, as no attempt was made to compensate Indian users by means of subsidised railway or bus services, which were arranged for both blacks and whites in other areas of Durban and elsewhere in SA (the Crossmoor, Chatsworth railway line was intended to serve the Indian community but was poorly thought out and has been a waste of money since its inception in the early 1970s).

The forgotten community

The Indian community in both Phoenix and Chatsworth had to fend for itself and, as Zainul’s book makes clear, succeeded remarkably well under difficult circumstances. Private bus operators had to rely on running at the lowest possible cost to enable them to offer affordable fares, while in other parts of Durban, the railway and municipal buses not only received large subsidies but had a hotline to the local transport board. This body did not hesitate to harass Indian operators, using its political muscle to keep them out of the central area. The metro police could also stop Indian operators on the road, something that was unheard of with Durban’s municipal bus service. Once the railway line to Chatsworth was complete, the railway tried unsuccessfully to shut the Chatsworth bus operators down. While the end of apartheid might have been expected to bring some relief to the bus owners, it merely coincided with the explosive growth of the minibus-taxi industry, resulting in unchecked competition which simply continued to eat away at the Indian bus passenger market.

A debt owed

The city council of Durban (eThekwini) owes the Indian community a large debt, and I would like to be the first to suggest that a well-thought-out legal challenge from the Indian community could force the city council (and by extension the provincial and central governments) to start acting on their responsibilities towards the public transport needs of the entire population of South Africa. A judicial precedent needs to be set, which all levels of government in SA should be compelled to follow. For many years now, there have been a number of court cases in public transport in which the judgement has gone against the government, the most recent being the judgement of the Eastern Cape High Court in favour of the Intercape bus company against intimidation from minibus-taxi operators.

Legal actions required

The financing of public transport in South Africa would be a good place to start legal proceedings. The unequal treatment of train, bus, and minibus-taxi passengers is profoundly unconstitutional and I would predict that a legal case brought by an organised group against the government will not only succeed, but will almost certainly be accompanied by a costs award in favour of the complainants. Whether a favourable judgement will actually move the transport needle in South Africa remains to be seen, but the prevailing mood in this country is that a growing number of people from all backgrounds have had enough of the incompetence and mismanagement surrounding the spending of public funds.

The demise of rail

While rail passengers enjoy heavily subsidised fares, other passengers do not. There is no academic, scientific, or technical reason for this. All users of public transport should pay the same fares irrespective of the mode used. The bus industry in SA, which has lacked strategic leadership for many years now, has been far too tolerant and – for reasons best known to itself – almost complicit in failing to challenge this.

Far too much money is being pencilled in for rail expansion (think Gautrain and Moloto Road – about R60 billion in all) and rail rehabilitation (think the R123 billion Prasa coach-building programme) when well-run bus services can do the job better in many areas. I further predict that the engineering and construction people, who love to trumpet the high capacity of rail, will be quick to huff and puff about the “need” for rail. Well, they haven’t been too vocal about the virtual destruction of SA commuter rail which commenced 40 years ago. Let’s be honest with ourselves – we are not serious about rail and need to stop pretending that we are. Rail has merely become an ATM for people who have no interest in transport but who are quite happy to get lucrative contracts to “fix” it.

Give up on Gautrain

A legal action against the government could rely to a significant extent on the scathing criticism of Gautrain by the Automobile Association (AA), dated August 2021. There seems to have been no follow up on this document, while Gautrain continues to hold meetings in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg giving the residents “options” to choose from in the determination of possible routes for its expansion. This should be stopped. Period.

Where is the progress?

Another problem group is the town planning profession, which sits in its offices all over South Africa, surrounded by large multi-coloured wall-mounted maps, deluding itself that it is “planning” a transport network. Many people have served out their entire careers developing “integrated” plans running to thousands of pages packed with pretty drawings, tables, and charts, but with no real progress to show for it. Anyone who thinks that Gautrain and BRT schemes represent progress should be reminded that Gautrain has been a financial disaster, while BRT schemes have achieved almost nothing that a much-improved basic bus service could not have achieved.

The only two significant developments in public transport in South Africa in the last 35 years are the Durban Mynah service introduced in 1987 and the Go George scheme of around 2016. Even these schemes can be criticised – the Mynah service has since fizzled out to almost nothing and Go George made use of brand-new buses. While nice to have, future schemes will have to start off with existing, used vehicles (yes, even unsuitable 15-seater minibuses at first) in view of SA’s financially distressed situation.

So, the way the eThekwini IRPTN ignores the private Indian bus companies is an indication of the real disregard from the government for public transport.

Private owners must learn to cooperate

None of this says that private operators have been blameless. Throughout Zainul’s book there are references to a lack of cooperation between bus owners. I would agree that not only Phoenix, but also other areas served by private operators, would “still have a lucrative bus service if the owners were united and formed a consortium from the beginning”, as one owner is quoted on page 33. “None of them had the foresight of what the future held for them in Phoenix.”

Private buses have operated for over 100 years now along the trunk North Coast and South Coast corridors, with an intensive service that would have justified electrification long ago – either light rail or electric trolleybus. Maybe the heavy hand of apartheid has resulted in a survivalist mode, which might explain the lack of new ideas such as new route initiatives, bus technology developments, and better fare collection methods. So, instead of offering more comfortable buses, they polished hubcaps, gave their buses exotic names, and fitted noisy sound systems, none of which are likely to attract new passengers in large numbers.

Looking Ahead

Future operations must also include proper timetables and information on websites and social media (which very few subsidised operators do properly) and more sophisticated ticketing systems. No doubt these improvements will raise costs, but I am confident that private Indian operators can still quote lower contract prices under a proper contracting system (that’s government policy by the way) than existing bloated rail and bus operators can offer. This leaves us with the problem of the unsustainable minibus-taxi industry, which will have to be the subject of a separate article.

I look forward to seeing a follow-up by Zainul, who hopefully has opened a can of worms with his fine book. His painstaking research is an example to other academics.

Published by

Focus on Transport

focusmagsa