The Cost to SA of the Logistics Bureaucracy Crisis

The Cost to SA of the Logistics Bureaucracy Crisis

As we look forward to 2025, it is relevant to identify the factors which impede the urgent action required to rectify our national logistics crisis. NICK PORÉE writes that this is essential, as the capacity for action of the current organisational structures is constrained by government debt.

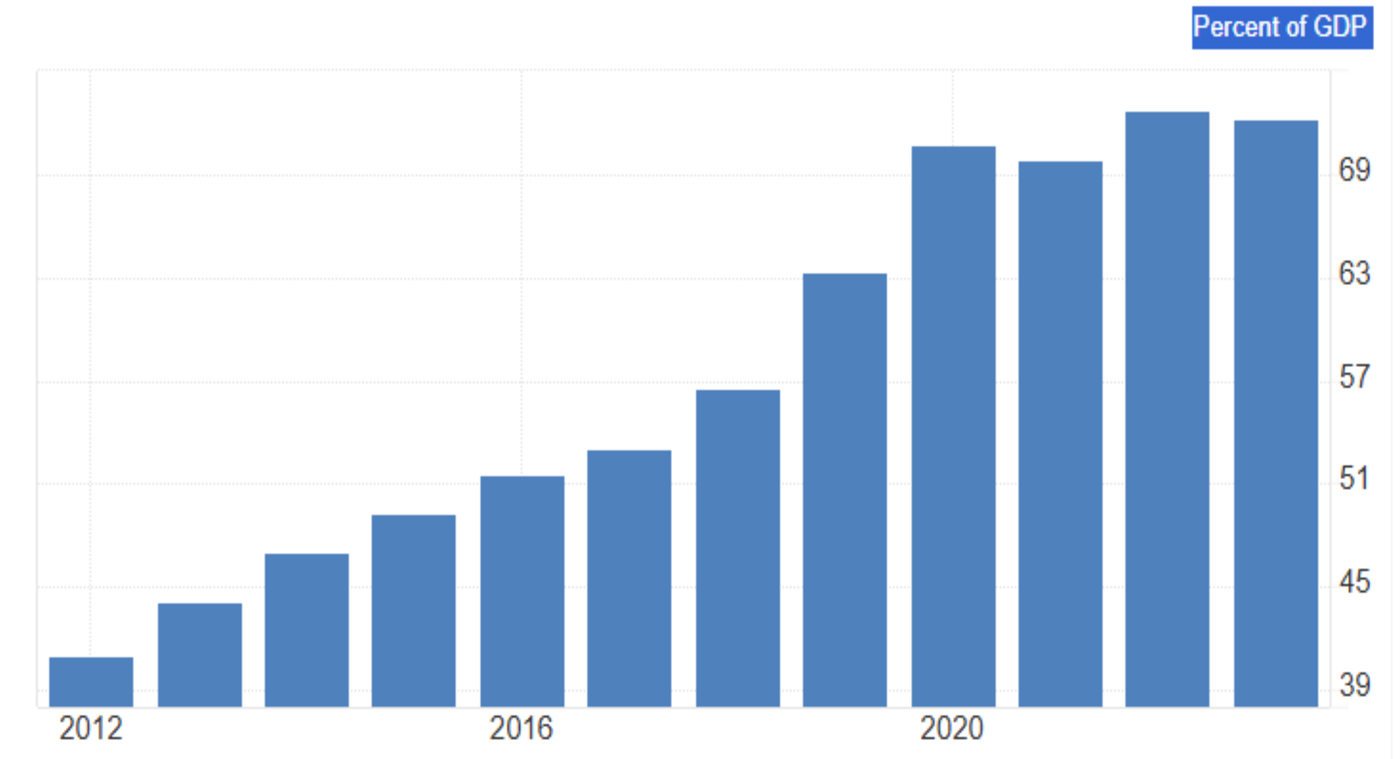

In common with many other countries, the impact of current government debt and failures by state-owned companies (SOCs) is having a limiting effect on opportunities for economic growth. It is, however, universally recognised that increased production is essential to reducing borrowing and debt. In South Africa, the ratio of government debt to gross domestic product (GDP) rose to 72.2% in 2023, requiring debt repayment of over R30 billion per month and raising possibilities of defaults.

The high level of debt (R553 billion) is the result of managerial incompetence, misspending, and corruption in SOCs and government. There is minimal evidence of any positive development from the expenditures incurred, but overwhelming evidence of the deterioration of SOCs and the failure to invest in maintaining and upgrading infrastructure in towns, water, roads, hospitals, and schools. The logistics crisis is just one element of the overall national governance failure, with impacts on railways, ports, borders, roads, industrial production, and export earnings.

Railway

According to an African Rail Industry Association (ARIA) response to the Transnet Rail Infrastructure Manager (TRIM) Network Statement, the impact of the deterioration of railway services and ports on the mining industry alone amounted to approximately R110 billion in 2023, with further losses to agriculture and other industries.

The structure of the Network Statement – produced by TRIM along with the Access Charges for 2025 (Gov, Gazette 51819) – is necessarily designed to protect Transnet interests and cannot be regarded as “open access” or “independent competitive conditions”, as sought by the private sector.

The tariffs are complicated by the multiple potential variations, which will require detailed analysis of each train configuration in order to assess charges. The tariffs do not include specific electricity charges, which must necessarily be included where relevant. The fact that aspirant Train Operating Companies (TOCs) will have to build and supply all facilities and equipment for handling breakbulk and intermodal cargoes is likely to be a sufficient deterrent to investment. Therefore, it will be necessary to spend another R100 billion on recovering Transnet Freight Rail (TFR) to 2020 standards, with no progress in creating a sustainable competitive commercial railway system.

Borders

The South African border posts are in desperate need of total overhaul and modernisation. The private sector design and modernisation of Beitbridge on the Zimbabwe side and the efficiency of the one-stop border posts (OSBPs) on the northern corridor in the East African Community (EAC) underscore the need for investment and professional commercial design to improve border processing capacity and reduce operating costs.

Weekly transport delay costs at South African borders show the impact on logistics, but may be greatly exceeded by the cost to industry and regional trade.

Year | Delay costs/week (ZAR) | Delay costs/year (ZAR) |

2021 | 11,500,000 | 598,000,000 |

2022 | 16,000,000 | 832,000,000 |

2023 | 13,500,000 | 702,000,000 |

2024 | 10,900,000 | 566,800,000 |

Total (4 years) | 51,900,000 | 2,698,800,000 |

Approximate annual cost of transport delays at South African Borders (2021-2024)

Source: FESARTA/BUSA Weekly Reports

Ports

Transnet has debts of R135 billion and has not been investing in port operational improvements for many years, but has been diverting ports profits to other areas of inefficiency. The Transnet National Ports Authority (TNPA) has asked the Ports Regulator of South Africa to increase its average tariffs by 7.9% during the 2025/26 financial year, by 18.61% in 2026/27, and by 2.52% in 2027/28. The tariff increase will make it more likely that trade will be rerouted to more efficient ports, including Walvis Bay, Maputo, Beira, Lobito, and Dar es Salaam, which are all taking market share from SA.

Container volumes and revenue are reducing, whilst the backlog of deferred maintenance, expansion, and modernisation of the ports will require billions of rands. With customers having to deal with port inefficiencies, persistent equipment failures, labour issues, and ship delays, one would expect TNPA to offer incentives to attract customers by keeping tariffs low. In practice, however, the massive expenditure backlog will dictate increased charges – by whoever manages the ports.

To further complicate future recovery, instead of the necessary wholesale revitalisation of the Port of Durban, a 25-year contract was awarded to the Philippines-based logistics firm International Container Terminal Services Inc. (ICTSI), to run, upgrade, and operate Container Terminal Pier 2. This has been successfully challenged by APM Terminals (Maersk) for procurement irregularities, meaning recovery will be further delayed.

According to Maersk, ship delays in Durban are 13 to 24 days as of December 2024. The estimated costs of ship delays in Durban for December are shown in the table below. The 3.2-day average per container vessel is not excessive, but the cumulative additional shipping costs contribute an additional R2.332 billion to annual maritime costs via the port.

Vessel Type | Number | Hours at Anchor | Days | Rate/day (US$) | Total delay cost (ZAR) |

Container | 93 | 77.99 | 302 | 24,000 | 130,555,260 |

Tanker | 69 | 38.64 | 111 | 27,000 | 53,989,740 |

Breakbulk (general cargo) | 15 | 39.93 | 25 | 22,000 | 9,882,675 |

Monthly total for 12/24 |

|

| 438 |

| 194,427,675 |

Estimated costs of ship delays in Durban for December 2024. Source: Linernet and NP&A

The Situation

The impacts of the logistics crisis amount to billions of rands in direct transport costs and even greater costs to industry from supply chain disruptions, loss of production, and markets. The overall scenario currently proposed to resolve the logistics crisis is a very expensive recovery at glacial speed, within the same organisational framework – back to where we were in 2019. There is zero vision of implementing a future dynamic, modern, integrated, commercially-competitive, multimodal logistics framework, and no analysis of the costs of the recovery to industry or the country.

The solution in 2025

SA’s manufacturing sector faces an urgent need for reform, and the shortcomings of the masterplan approach underscore the importance of adapting industrial policy to meet economic realities rather than socio-political illusions. The logistics crisis has occurred at zero GDP growth and the lack of transport capacity will inhibit economic and industrial growth. By transitioning to productivity councils and fostering an export-led growth model, SA can strengthen its industrial base, create more jobs, and improve its economic resilience.

The SOC service providers in the transport and logistics sectors are incapable of a rapid response to the very extensive requirement for both investment and professional commercial management to rehabilitate and modernise systems, facilities, and equipment. There is therefore an urgent need for alternative action and mobilisation of the expertise and capital in the private sector.

There is growing consensus that the solution to the current crisis of government is for action to be taken by those who actually run the productive economy which pays for the excessive costs of an ineffective government with an annual wage bill currently sitting at R721 billion (10% of GDP).

This cannot be reversed through talk alone – no matter how hard our leaders might try – using cooperative committee participation in government plans. The situation requires action: a fundamental shift towards greater individual freedom and self-reliance, along with the removal of key obstructive dirigiste impediments to growth and investment.

As noted by former statistician-general Dr. Pali Lehohla, “The solutions are in leadership. It must be a two-month discussion, ensuring what leadership it is. It must be led by people who are not government. It must be led by people who don’t have any interest in political occupancy.”

Truly, the words of 18th century Irish philosopher and politician Edmund Burke are also relevant here: “When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.”

Published by

Nick Porée

focusmagsa