Skills shortage could bring industry to its knees!

Skills shortage could bring industry to its knees!

It is becoming more and more difficult to find people with the skills to keep trucks on the road. NICK PORÉE warns that the transport industry could find itself in dire straits as a result.

One of the most serious threats to the transport industry’s future (in all modes) is the increasing difficulty of maintaining and repairing vehicles and equipment, due to the decreasing availability of technical competence. The continual upgrades in design, performance, and sophistication of imported heavy vehicles is lauded in industry magazines, providing evidence that the local industry is in touch with the advancing technology of First World OEMs. This is all good and necessary, but creates insoluble problems when these machines journey outside the major cities and across borders, where vast areas have no trained technicians, or even maintenance and repair manuals.

The situation is further aggravated by the recessionary economic situation, which is forcing stockists of components and spares to reduce inventory and change re-order levels to minimise costs. In rural areas it is common to be told that out-of-stock orders will be supplied ex-Johannesburg or Cape Town. For many machines in regular daily service, even routine servicing parts such as filters and brake components are placed on order due to nil stockholding. The downtime and loss of income can be fatal to small businesses; for farmers, the delays to preparation and planting can jeopardise an entire year of crop income.

Diesel mechanic: a critical skill

The Department of Higher Education produces a National Critical Skills List – the brainchild of the National Planning Commissars. The occupations of diesel mechanic, auto mechanic, and auto electrician have been on the Critical Skills List since 2014, with no serious attempts at rectifying the matter and no evident concern for the resulting threats to industry and society. Roadside vehicle surveys show that 60 to 70% of heavy goods vehicles are unroadworthy. The Road Safety statistics show 26 fatalities per 100 000 people with increasing truck-related disasters (compared to three to five in the developed world), but the connection between regulatory standards, managerial responsibility, and technical competence is unlikely to be apparent to civil servants who have never managed businesses.

A primary reason for the technical skills shortage is the demise of the national apprenticeship system, and the switch to TVET colleges has simply aggravated the problem without offering the means to restore training capacity or competent outcomes. The few totally competent training institutions in the country – run by major corporations for their own purposes – cannot even begin to supply sufficient technicians for the industry in the future, even if there was a pool of suitable trainee candidates, which there is not. The current skills deficiencies are apparent now, at zero GDP growth and with the de-industrialisation of the country. Future transport capacity to support industrial expansion will be restricted by many aspects of the current situation, especially the very real skills deficiencies in managerial and technical disciplines. As George Bernard Shaw said: “Action is the road to knowledge.”

Maths abhorred by students

The deplorable incompetence of the national education system is a fundamental problem blocking the creation of technical competence due to the erosion of adequately trained teachers. According to the Department of Basic Education, 750 478 students wrote matric exams in 2021, but only 259 143 wrote mathematics. Of those who wrote, 34 451 passed maths with 60% (a pass rate of 5%). This is the total of annual “marginally trainable” matriculants released to industry or universities for technical further education. The current system which sends applicants to universities without an entrance examination is a ridiculous waste of money, as it is totally impractical to enrol students for a technical course in any discipline requiring adequate knowledge of mathematics. This is further aggravated by inadequate English comprehension which makes engineering, chemistry, and statistics textbooks incomprehensible.

Managerial training has been totally scrapped since 1996 with the restructuring of the National Certificate and Diploma courses at the University of Johannesburg to accommodate the National Qualifications Framework (NQF), instead of serving industrial efficiency. There is a small ray of light, though: Stellenbosch University (which ran the first Transport Managerial Training Course in 1967 under Dr Cees Verburgh) will offer a practical course on Management in Road Freight Transport from 2023. The course is designed to enable working aspirant managers to study at home to qualify, and to enable enrolment and sponsorship of potential supervisors and managers by companies wishing to add qualified staff to their succession plans. Interested individuals can contact javrens@sun.ac.za.

In any future planning to recover the skills deficit, one apparently insurmountable problem facing the industry is the rapidly approaching situation where there will be no competent and qualified journeymen available to mentor trainees. It is universally acknowledged that a four- to six-year apprenticeship working with a competent mentor is a requisite for professional competence; book learning and classroom education cannot substitute for workplace experience. Most current workshop training simply produces “parts exchangers” without the diagnostic skills of true professionalism.

No solutions from seta

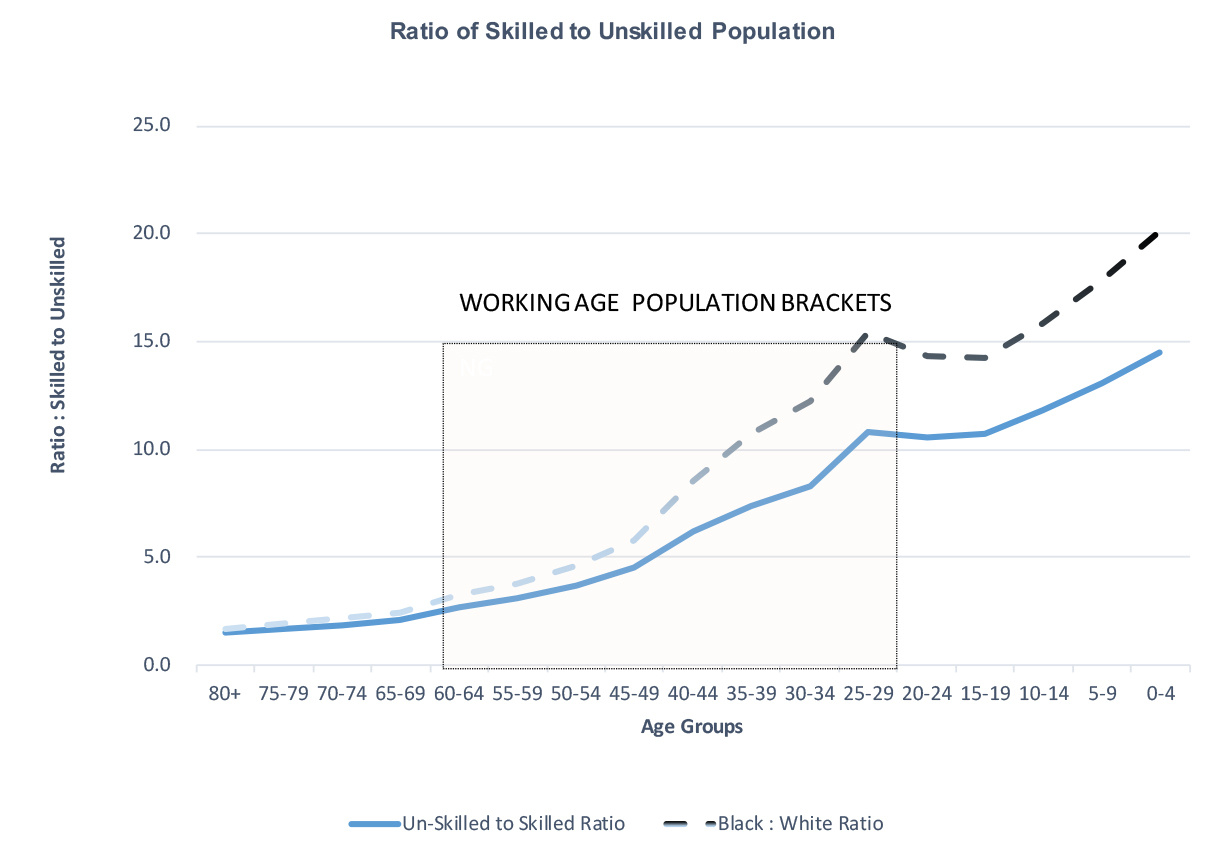

In 2016, Dr Pali Lehohla of Stats SA shed light on the dynamics and context of South Africa’s employment and unemployment, and discussed trends in employment over the past 21 years among those who are skilled. His analysis showed that the proportion of potentially skilled students from the government education system is likely to continue to disappoint learners, industrial employers, and policymakers for the foreseeable future. Current industrial training within the Sector Education and Training Authority (SETA) framework is not solving the problem, as it is institutionally linked to the NQF with its unrealistic academic perspective of education. The system produces graduates with certificates but limited usable skills for industrial purposes, resulting in a toxic mixture of wasted money and inflated expectations. It is relevant to note the inevitable future deterioration in the ratio of the skilled to unskilled population by age group, as shown in the diagram.

Using the statistics from the last available national census, the skilled:unskilled ratio at age 44 in 2015 was approximately 8.5:1, with unemployment at about 26%. With the increasing age of the same population groups, the ratio widens to 15:1 over the following 20 years and then to 20:1 by about 2050.

The situation in 2022, with over 40% unemployment, can only get worse without serious interventions. The current recessionary conditions and reduced viability and profitability of businesses are contributing to the growing trend of the emigration of skilled people in all occupations. This is evident in agriculture and most technical sectors, reducing the pool of technical and managerial skills so that unemployment can only increase exponentially. Yet even in light of the obvious future dangers shown by these irrefutable data, there is still resistance to permitting skilled immigration and effective education and training.

Published by

Nick Porée

focusmagsa