Road freight regulations in SA: change desperately needed

Road freight regulations in SA: change desperately needed

Some road freight regulations in South Africa are in desperate need of change! So says NICK PORÉE, who also has some suggestions about how these rules can be fixed.

There are several aspects of the road freight regulations in South Africa that are either anomalous or illogical and pose limitations on optimum productivity. Unfortunately there has been no single dedicated competent body to address these issues since the demise of the National Institute for Transport and Road Research (NITRR) in the 1980s. Some legislation is simply archaic, some is irrational, and some is simply impracticable. Here, I analyse the regulations and propose rationalising them for improved productivity and cost-effectiveness.

First, the steering axle definition in Regulation 240 of the National Road Traffic Act is an archaic leftover from the standards in the Provincial Road Traffic Ordinances, which were derived from the Tredco manual. The definition of tyre loading at 7 700 kg for a steering axle was based on the standard for 2 x 11.00: 20 Cross-ply tyres at 480 kPa and persists despite the fact that cross-ply tyres disappeared from the road about 30 years ago. Reg. 240 should be changed to 8 000 kg to harmonise it with the Tripartite region.

Secondly, the current maximum permissible vehicle height is 4,3 metres for all vehicles except passenger busses which may be 4,65 metres high (Reg 240). Some relief is offered to carriers of over-height loads such as high-cube containers by the provincial or Road Transport Management System (RTMS) permit system, which permits 4,6 metres for car-carriers and some other vehicles in terms of the public-private partnership arrangement sanctioned by the Department of Transport. This provides compatibility with Zambia (4,8), Zimbabwe (4,65), Tanzania and Malawi (4,6), and will support a harmonised Tripartite height regulation. The RTMS system can also offer improved payloads and extended vehicle lengths of up to 30 metres. This is an obvious benefit for the 60% of freight which “cubes out” before attaining permissible Gross Combination Mass (GCM) and is a potential high-productivity option for double container transport by road, which could be introduced without the need to change regulations.

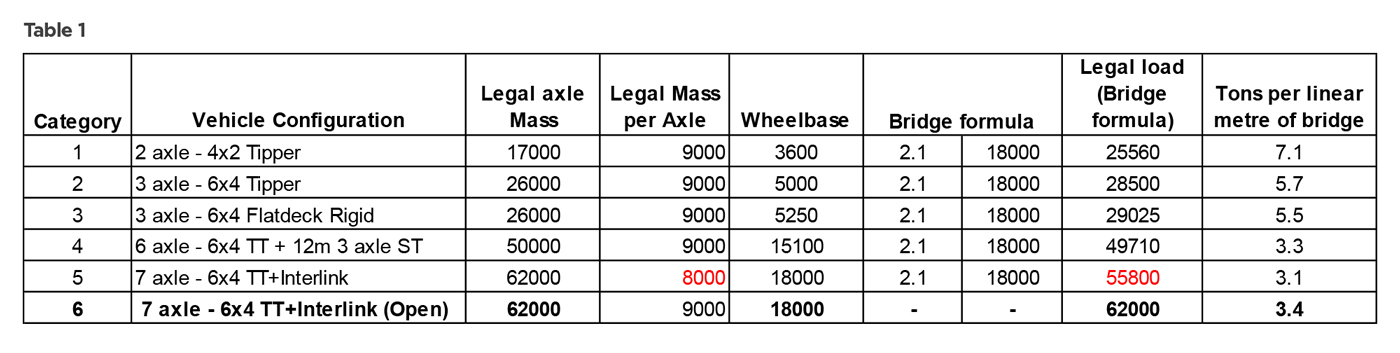

Next, the current Regulation 237 limits maximum GCM to 56 000 kg and accounts for a large proportion of the “overloading” recorded by weighbridges. The regulation is another illogical historical anomaly designed to “protect the railways from competition” that should be corrected. The railway switched to “train load only” cargoes about 30 years ago. The illogical nature of the regulation can be seen in Table 1.

The standard legal mass load (LAM) for axles with four tyres was increased to 9 000 kg in about 1987. This applies to all configurations from 1-4 in the above table. But, due to the abovementioned political intervention, seven-axle vehicles are restricted to 56 000 kg GCM – which effectively limits them to 8 000 kg LAM.

In order to motivate the 56-tonne restriction, a “bridge formula” was created as defined in Reg 241. The formula is “wheelbase in millimetres x 2.1 + 18 000 kg”, which is supposed to prevent damage to bridges and structures by limiting the point loading on bridges. The effect of the regulation can be logically measured as “tonnes per linear metre” of bridge length. As shown in the last column of Table 1, the formula as applied to various configurations does nothing to regulate point loading, as shorter vehicles impose double the point load of interlinks. If Reg 241 is necessary, (and there are many other ways to limit bridge loads), it should be redefined by a bridge engineer next time round.

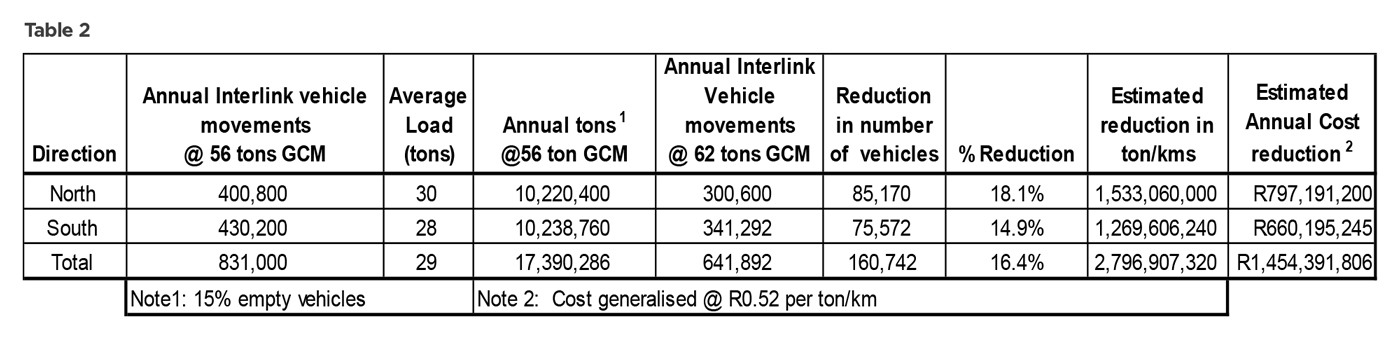

There is no logical reason for Regulation 237, as the total annual tonnage conveyed on a road results in the passage of a certain number of axles of whatever LAM. Table 2 shows the approximate annual tonnage conveyed by interlink and longer combination vehicles on the N3 national route between Durban and Gauteng.

Reducing the LAM increases the number of vehicles, and increasing the LAM reduces the number of vehicles used to convey the same tonnage. It can be calculated that if the standard 9 000 kg LAM was applied to all the axles of the larger vehicles (Cat.6 – Table 1) the number of vehicles required to convey the same tonnage would be reduced by 160 742 vehicles per annum (16,4%), thereby reducing congestion and giving a transport cost saving of about one billion rands a year.

With these changes, the complicated terms of the National Road Traffic Act (Part IV): Loads on Vehicles could be simplified and overload control (which is primarily supposed to protect roads) could be focused only on measurement of axles exceeding 8 000 kg front axle and 9 000 kg for all other axles. This would facilitate High Speed Weigh-In-Motion (HSWIM) and effective monitoring of freight transport via an integrated database receiving the data from Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras and system-generated online warnings supported by evidence, as well identification of serial offenders and many criminal situations for more stringent action. The decriminalised overloading offences can then be reduced to antisocial payments in ”rands per kg” on an exponential scale for excess weights, and online settlement by registered operators. This will reduce enforcement costs and increase effectiveness and efficiency by the use of available technology.

Published by

Nick Porée

focusmagsa