Free trade and dispute resolution

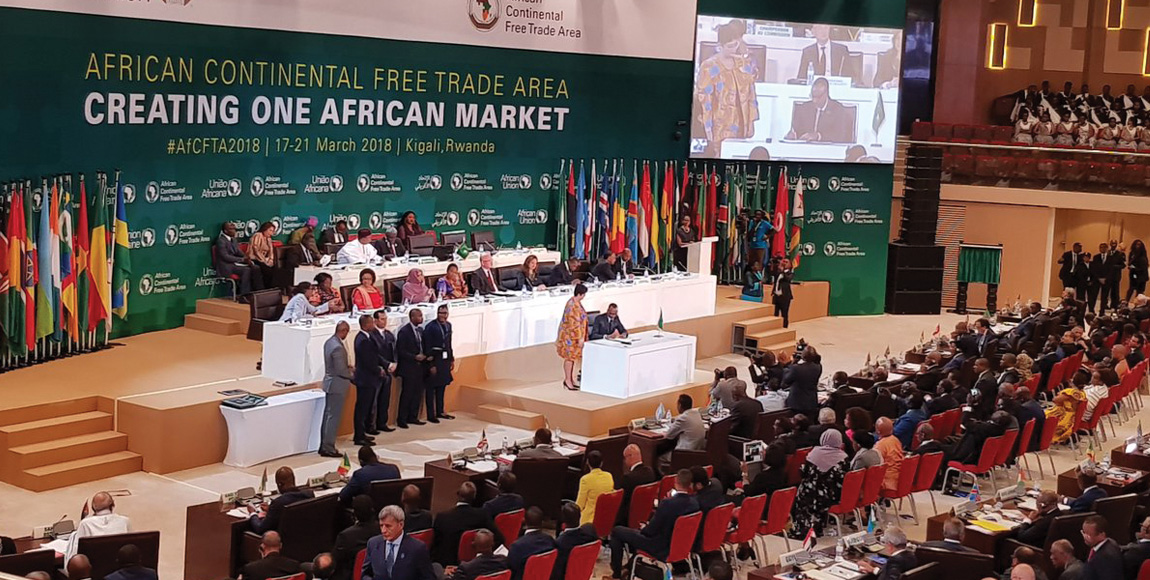

If the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement enters into force later this year, it will give member states a mechanism to resolve disputes and promote trade.

AfCFTA needs 22 ratifications before it enters into force. Currently 19 of the 49 signatories have ratified it and a further nine ratifications are expected in 2019.

When it comes into force, it will not automatically dissolve and replace other regional trade agreements across the continent. The levels of regional integration between member states of regional trade agreements will remain. The AfCFTA will provide a mechanism for the settlement of disputes between states in accordance with certain rules and procedures.

As African states do not generally sue each other, the AfCFTA will introduce an alternative dispute-resolution process to facilitate consultations and negotiations, rather than a strictly judicial procedure. The agreement will do so by establishing a Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) to facilitate disputes between states.

If a dispute arises, in the first instance, states will hold consultations to find an amicable resolution. Any requests for a consultation should be channelled to the other state through the DSB. These consultations will be confidential and without prejudice to the rights of the involved state.

Where consultations fail, the DSB will establish a Dispute Settlement Panel for formal resolution. The DSB (through the Panel) will then make a final and binding decision. This decision can be appealed to the Appellate Body (to be established by the DSB).

Interestingly, state parties to a dispute may mutually and voluntarily agree to refer the matter for conciliation, mediation or arbitration as alternatives to referring it to the DSB.

If the parties agree on arbitration, they will need to agree on the arbitration procedures. It is likely that the Model Law by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law will feature in many of these arbitrations.

The DSB will also keep tabs on state parties’ implementation of their (or the Appellate Body’s) rulings and recommendations. Failing compliance, the DSB may impose temporary measures including compensation and the suspension of concessions.

It appears that only state parties will have the standing to make use of the dispute settlement mechanism in terms of the AfCFTA. It remains unclear by which body a dispute can be referred from the general populace of one of the state parties, or by any other interested party should this ever be necessary.

Currently, the South African Development Community (SADC) tribunal also does not allow any private parties to bring cases to it. The mechanism to settle inter-state disputes is welcomed as it should facilitate trade between member states.

A similar approach could be adopted to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa) and the East African Community (EAC) Courts of Justice. They require the exhaustion of all local and possible internal remedies (within a state) before allowing an issue to be ventilated internationally.

We are enthusiastic about the prospects of the AfCFTA. Having such wide-ranging discretion for states to settle disputes through alternative dispute-resolution procedures, and not simply a strict judicial process, is likely to facilitate and encourage resolutions and pave the way for further partnerships between states.

Published by

Richard Steinbach

focusmagsa