Conquering the globe with a Silk Road

Independent Chinese truck drivers are struggling despite growth in the gig economy, while the government plans to revive its ancient Silk Road trade route. MARISKA MORRIS investigates the situation in China.

In March 2015, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang unveiled the Internet Plus plan. According to China Daily, its purpose is “to integrate mobile internet, cloud computing big data, and the Internet of Things with modern manufacturing, to encourage the healthy development of e-commerce, industrial networks and internet banking, while getting internet-based companies to increase their presence in the international market.”

The plan encouraged freelance work in a response to the slowing of the Chinese economy, which resulted in the growth of a gig economy – an environment in which temporary positions are common and organistions contract with independent workers for short-term engagements.

Today, China has one of the biggest gig economies with over 110 million people. It accounts for about 15 percent of the entire labour force and is expected to quadruple by 2036. It indirectly contributed 8,1 percent to the Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016.

However, Viola Rothschild, in an article for Foreign Policy, notes: “The growing pervasiveness of the gig economy has raised serious and pressing concerns within China about workers’ access to social insurance, compensation, pensions and health care.”

The Chinese transport and logistics industry has also been impacted with an estimated 90 percent of commercial transport vehicles being individually owned. The industry handles around 220 trillion yuan (R465 trillion) of goods with logistics costs accounting for 15 percent of the Chinese GDP, yet the majority of transporters stand idle for 40 percent of the day.

Anjani Trivedi, in an article for Bloomberg, writes: “Every morning, Chinese drivers gather at hubs, waiting out an offline, auction-like process that matches shippers and truckers. Then they travel to logistics parks to pick up the goods – which sometimes aren’t there.”

Manbang is a platform that connects shippers with truckers. It brokers agreements and takes 20 percent of the commission. It has signed up 5,2-million truck drivers and 1,2-million shippers.

“A big wrinkle in Manbang’s valuation is costs. In June, truckers went on strike to protest rising fuel prices and other expenses like tolls, fines, and the app’s impact on haulage rates. The fragmentation in the industry means drivers don’t have much bargaining power,” Trivedi writes.

Manbang’s dominance in the industry has resulted in independent truck drivers reducing fees and accepting longer trips with increased fuel prices eating into their small profit margin. However, Manbang faces its own cost concerns. The company loses an estimated one billion yuan (R2,1 billion) a year on capital expenditure and payroll.

Executive chief editor of CVzone, Shao Zitong, notes that if the estimated population of 30-million truck drivers is phased out completely, it will have a disastrous effect on the country.

“Everyday life in China will be in total chaos. Road transportation made up 78 percent of all the transport in China in 2017. It will especially affect the popular e-commerce industry. Online retailers depend on truck drivers and couriers,” Zitong says.

To ensure that drivers continue their work, Zitong suggests: “More regulations are needed to ensure the welfare and health of truck drivers. With the Non-Truck Operating Common Carrier (NTOCC) mode coming into play and spreading, the competition is not healthy. The freight transport price is much lower than before, which makes it hard for drivers to earn money.”

She adds that even though apps that are used to manage drivers had a good goal initially, they place too much pressure on the drivers. “Drivers cannot even stay at the service station for more than 20 minutes before they are contacted; despite the need for them to rest after several hours,” she explains.

Zitong notes that truck drivers need more respect in China. It is not a well-known or respected job. There are fewer young people interested in truck driving as a career.

However, this could be a blessing in disguise as China implements its Belt and Road initiative, which will move some road transportation to rail and waterways. The initiative will see the revival of an ancient trading route dubbed the Silk Road. Zitong argues that the transport and logistics industry will greatly benefit from the initiative.

“With the support of the national Going Out policy (a strategy to encourage Chinese enterprises to invest overseas), more investments will come from the government and some cooperation platforms will be established between construction and operations,” she explains. Increased investments will provide more opportunities for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and logistics companies to develop their businesses overseas.

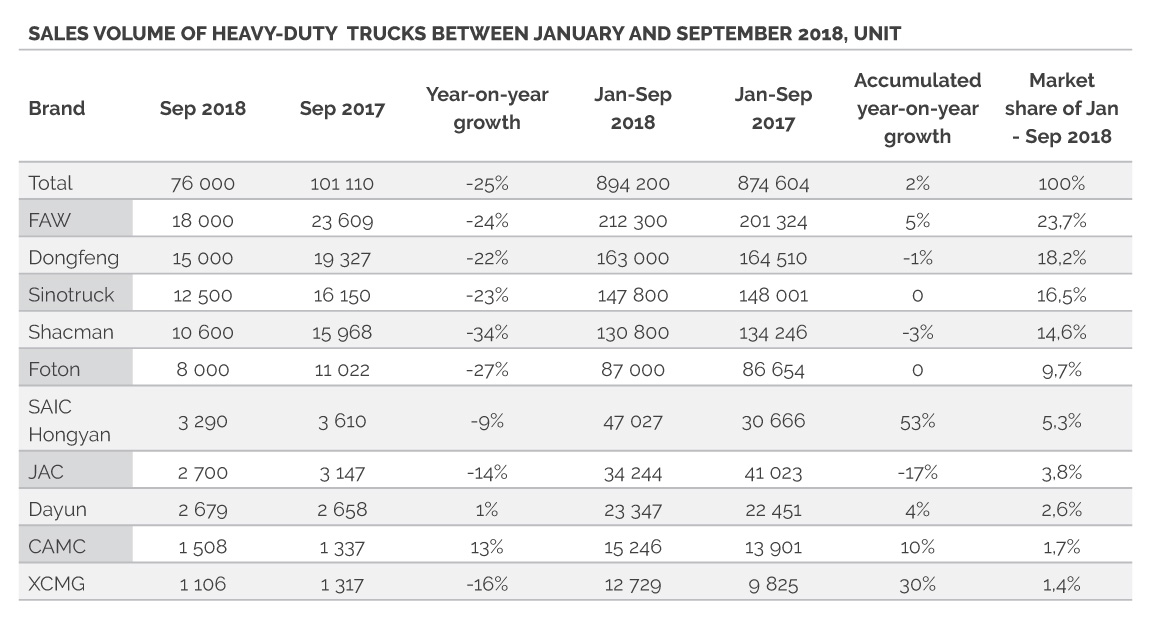

Sales of heavy-commercial vehicles in China are suffering. Zitong notes: “In September, the total sales volume of heavy-duty trucks was 76 000, a slight increase of six percent from August, but a sharp decrease of 25 percent since 2017.”

A statement by the Chinese government, which was shared with FOCUS by Zitong, notes that the three-year Belt and Road plan aims to push the restructuring of the transport industry to reduce pollution, increase efficiency and lower logistics costs.

“The country will witness a 30-percent increase in transportation by rail, (or 1,1-trillion tonnes) and waterway transportation will increase by 7,5 percent (or 500-trillion tonnes) by 2020. The road transportation volume for bulk cargo will see a reduction of 440-billion tonnes,” the statement reads.

While the initiative threatens the livelihood of many independent transport operators and could see further sales declines for Chinese OEMs, it does promise to further boost the Chinese economy, which might create more employment opportunities and empower businesses to expand their companies to various other countries.

Published by

Mariska Morris

focusmagsa