Freight transport: do or die?

Freight transport: do or die?

Is the land freight transport system in South Africa, consisting of road and rail, broken? More importantly, can it be fixed? ELVIN HARRIS takes a cold, hard look at this pressing issue.

Transport systems are never static. They are always evolving, based on the needs of the local and global economy and the policy directions determined by governments and other major role players in the transport system and the real economy. This is done with the primary objective of adapting the system to be current and supporting the competitiveness of firms, industries, and supply chains as the economy expands, develops, and becomes more sophisticated.

Perhaps a quick reminder is needed from Transport Economics 101: in its very essence, transport is a derived demand, not something that exists in and of itself. It arises only out of the need to enable place and time utility of people, and goods being needed at a different place and time than their origins.

Apartheid impacted policy

Policy-wise, the land freight system in apartheid South Africa was set up to support particular political and economic objectives of the government of the time. Critically, spending priorities of the apartheid state reflected its policy agenda. Whether this agenda was good or bad is another matter.

Despite many other policies and legislation of the pre-1994 government, insofar as the transport sector is concerned, probably the most impactful changes to the system were made during the 1980s when, following the publication of the De Villiers Report on the Management of the South African Transport Services in 1986, the government of the day passed the Transport Deregulation Act of 1988, the Road Traffic Act of 1989, and the Legal Succession to the South African Transport Services Act of 1989 that established Transnet SOC Ltd, as well as created the South African Rail Commuter Corporation (later to morph into PRASA).

The post-apartheid/democratic government has set out large-scale reviews of government policies since it came to power in 1994. Major policy and strategy reforms were undertaken, and new policies and strategies were adopted for implementation by government, role players, and stakeholders to reflect the democratic government’s political and economic objectives. From a transport perspective, out of the many policies, strategies and pieces of legislation that were introduced since 1994, I will only refer to a handful in this article, namely the Reconstruction and Development Programme, or RDP (1994); The White Paper on National Transport Policy (1996); Moving South Africa (1998); Moving South Africa: The Action Agenda (1999); the National Freight Logistics Strategy (2005); the National Transport Masterplan (NATMAP – 2009); The National Development Plan (2011); The National Road Freight Strategy (2017); and the most recent White Paper on National Rail Policy (2022).

Without going into the details of the objectives of each of the above-mentioned policies, strategies, and enabling legislation, they can be reduced to the following overarching statement: “Improve the transport system to better serve the economy and the needs of users of the system to enhance their competitiveness, doing so in an environmentally responsible/sustainable manner”.

The new policies, strategies, and legislation – and their corresponding objectives – were clearly designed to “correct” policies, strategies, and legislation of the past that were no longer aligned with the new political dispensation and the concomitant new socio-economic agenda.

One could argue, if able to momentarily set aside questions of morality and fairness, that the land freight transport system prior to 1994 was largely functional, efficient, and contributed to the competitiveness of the economy (such as it was at the time). Some 30 years on, can the same be said of the present system, or is the land freight transport system broken?

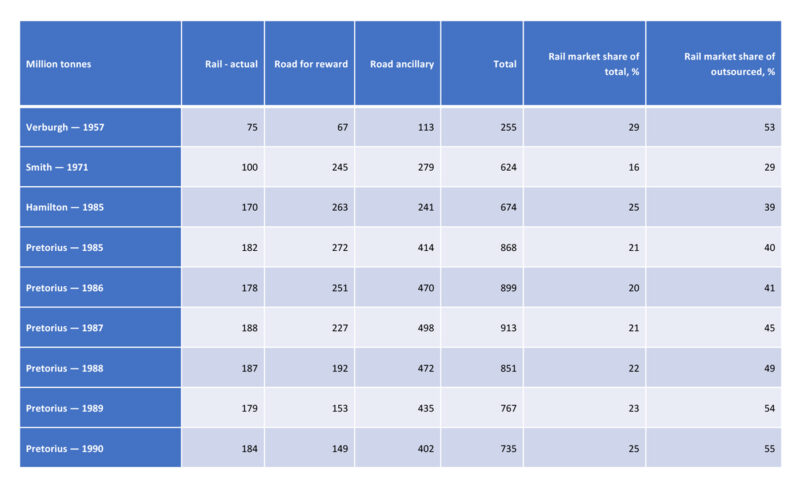

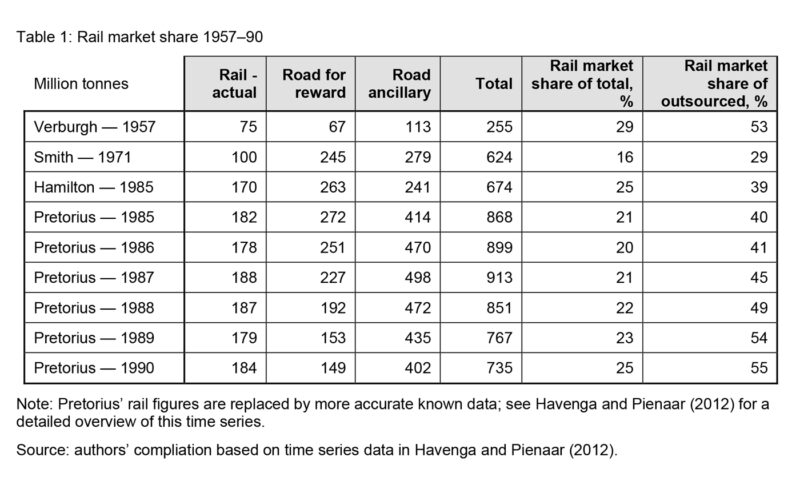

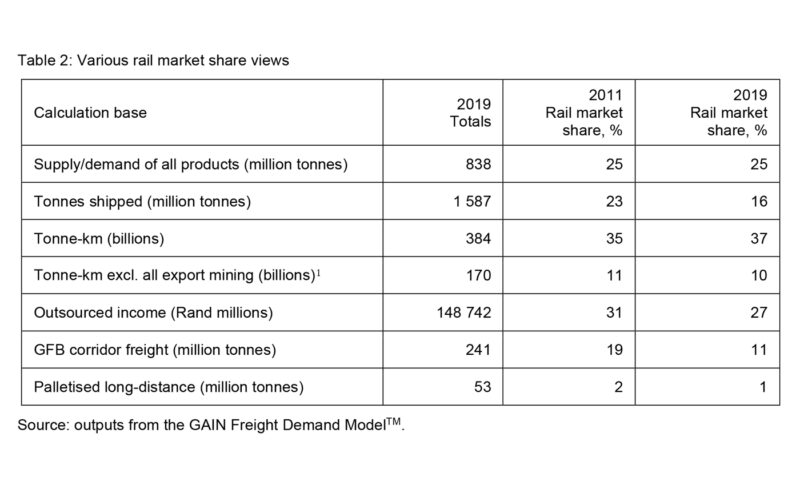

Although rail market share has kept steady for bulk commodities, the data displayed here, which was confirmed most recently in a 2021 Southern Africa – Towards Inclusive Economic Development (SA-TIED) report by Jan Havenga et al., clearly shows that rail freight market share for long-distance corridor traffic has significantly declined over the past two decades. This is a very worrying picture for rail freight transport, but it also has a major impact on the total land freight system.

It is very worrying because long-distance corridors longer than 350 to 400 km should be the ideal segment for rail freight to dominate the space. Yet, it is in this very segment that rail freight has lost the most market share and seems to be the least competitive. This level of decline in rail and consequent imbalance between road and rail freight transport surely indicates that the system is broken to at least some degree and that it does not support the competitiveness of the South African economy. Indeed, rather than contributing to and enabling competitiveness, it is hampering economic performance.

If the land freight system is indeed broken to at least some degree, the question then becomes: can it be fixed, and if so, how?

In answering the above questions, two critical factors need to be considered:

- The distance between major centres of extraction/production/manufacturing and the seaports.

- A set of advantages cumulatively obtained by road freight transport over rail freight transport since the Transport Deregulation Act of 1998, causing an unlevel playing field skewed towards road freight. These include a high GVM limit of 56 tonnes; high levels of overloading of freight trucks; lack of enforcement and low levels of prosecution against offenders; high externality costs that are not internalised, but carried by taxpayers; avoidance of national roads, weighbridges, and traffic police by truck drivers; and, perhaps debatably, insufficient contribution to road infrastructure by the road freight industry. Furthermore, the level of investment that has gone into the land transport system since the 1980s also needs to be considered.

The charts indicate that road freight demand is expected to triple from 300 to 900 billion tonnes/km as the economy grows over the next 30 years. Demand for rail freight will surely increase in a similar manner. As at 2013, the condition of the road network was not great overall, with less than 20% of the road network classified as “excellent” and a further 20 to 30% classified as “good” by official sources. There has no doubt been a further decline in the quality of the road network over the ensuing nine years.

On the rail freight side, it is understood that the heavy haul bulk lines are in good to excellent condition, while the general freight network, including branch lines, is not. The investment picture for road vs rail shows that since 2008 the road network has received over 10 times the amount of investment as the rail network. On the other hand, the backlog in maintenance spend for the rail network in 2018 was R63.9 billion compared to R197 billion for the road network. Spending priorities over the past two decades clearly did not reflect the key policy agenda of shifting cargo from road to rail.

Much work and money needed

So then, can the land freight transport system be fixed? Yes. But only if the road/rail imbalance is corrected with urgency and huge amounts of money are thrown at the under-investment problem to significantly increase investment in rail freight especially (but also on road freight) to keep up with the burgeoning demand.

The maintenance backlogs in both road and rail need to be addressed immediately if the land freight system is to fully support and enable the competitiveness of the South African economy. In addition, the scourge of economic sabotage on the rail network through cable theft and other forms of vandalism needs a concerted programme of decisive response, otherwise it will continue to cripple the system. The major stumbling block, unfortunately, as we know, is that government doesn’t have money to throw at these particular problems.

It took 30 years for the rail/road imbalance to switch from 90/10 to 15/85. The ideal balance is somewhere around 30/70, given the nature of the SA economy and the geographical spread of the transport task. This is unlikely to be achieved in under 10 years, even if everything goes right towards such a reversal!

Meanwhile, insofar as huge chunks of investment into the system and especially the railways are concerned, the public sector is looking to entice the private sector to come up with the money. Noting the utterances from leading private sector players since the launch of the White Paper on National Rail Transport Policy, this is unlikely to gain much traction soon either. And if, by some miraculous about-turn, the private sector does come to the party sooner rather than later, it will still probably take 10 to 20 years to roll out all the investment required, for technical and practical reasons alone.

Thus, 10 years from now we may not have a viable freight railway in South Africa as we know it today. Government needs to refocus its efforts on a small number of critical elements within its control and have a rethink on how it can entice the private sector to contribute to fixing this mammoth problem. We need to learn from the setbacks of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Programme and avoid repeating them in the rail space.

Failure on the part of all actors – public and private – to respond with the necessary speed will inevitably result in the system being rendered beyond the scope of repair and we will have to do the best with what remains of a dysfunctional land freight system. This will be a massive blow to the South African economy and the transport, logistics, and supply chain professionals intent on crafting optimal solutions for the clients they serve.

Can the land freight transport system be fixed in the short term? In my view, no.

Collapse looms

For the short term, we will have to continue to endure the pain of a dysfunctional system, which is likely to get worse if tangible steps on major issues are not taken as a matter of urgency. Furthermore, if no real tangible actions are taken now (not just nice words, speeches, strategies, policies, and legislation) I’m afraid the land freight system will reach a state of collapse within the next 10 to 15 years.

Our freight rail system will likely be reduced further and the burden on the road network, already in an average condition overall, but with a nearly R200-billion backlog on maintenance, will simply not be able to cope with many tens of millions of tonnes of additional cargo.

This warning of system collapse has been given since Moving South Africa in 1998/99. I fear we have now run out of time for posturing. What needs to be done is not rocket science. All the policy and strategy documents referred to above developed by the democratic government, including the most recent work done by Operation Vulindlela and the SA-TIED report, have described what needs to be done. By and large, the strategies and policies have failed to achieve their desired outcomes due to a lack of action. We cannot continue sitting on the fence with tough choices while Rome burns.

I used to be an eternal optimist about fixing the system. Now, however, while confident that we can (if we get our act together and act in concert), I’m not so sure that we will.

This thought piece and the questions being posed relate specifically to the land freight transport system in South Africa. It does not purport to offer any views on the public transport system in the country.

Published by

Elvin Harris

focusmagsa